It's unfair to assume that audiences attending cinemas during the turbulent period of 1928 to 1930 weren't discerning or sophisticated, and were lured into theaters primarily by force of habit and the added incentive of such technical innovations as sound and color. To the contrary, public dissatisfaction with particular performers, types of movies and imperfect reproduction was closely monitored and, for the most part, heeded to by studios unwilling to risk revenue loss.

Then as now, when something new shows even the faintest signs of wide popularity and acceptance, the public is bombarded with more of the same until a saturation point is reached and a backlash begins. Such was the case with film musicals and, to a lesser degree, films photographed in various color processes --- both of which skyrocketed in numbers throughout 1929 and would peak in mid-to-late 1930. At this point, weary of the endless aural tumult and eye-straining poorly printed color films, the tide turned and a general dissatisfaction was made plain by both audiences and critics alike.

An exploration of color films of the early sound era is badly warranted, but beyond the scope of this forum, and, admittedly, the author. So rather than attempt to (badly) explain the "why" and "how" of these films --- most of them lost to time --- it's more within my ability to focus a spotlight on a particular title or two every now and again, some familiar to readers, others not.

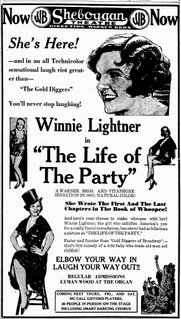

An infrequent cable airing recently of the 1930 Warner Bros. film "The Life of the Party" presents us not only with a very different film than audiences originally saw, but also rather different than the film the studio set out to make. Filmed entirely in Technicolor, "Life of the Party" would retain it's hues (although not most of it's music) by the time it reached cinema screens, yet it can only be seen today, for a variety of reasons, in black and white.

An infrequent cable airing recently of the 1930 Warner Bros. film "The Life of the Party" presents us not only with a very different film than audiences originally saw, but also rather different than the film the studio set out to make. Filmed entirely in Technicolor, "Life of the Party" would retain it's hues (although not most of it's music) by the time it reached cinema screens, yet it can only be seen today, for a variety of reasons, in black and white.The loss of Technicolor doesn't particularly harm the film or hamper enjoyment of the simple plot, but it was clearly once as much a part of the show as it's stars, Winnie Lightner, Irene Delroy and Charles Butterworth. Such sequences as the opening montage of brilliantly illuminated nighttime Broadway, a fashion show, and the highly ornate and spacious hotel in which much of the action is staged, all must have been a feast for the eyes in the muted pastels of the two-strip Technicolor process.

When color footage surfaces for films we've previously only seen in monochrome, the effect can be awesome. Details in costume and setting that once were hidden in murky gray film grain suddenly spring to life and catch the eye, and with it the very actors on the screen themselves seem to move and breathe with a renewed vibrant life spark that wasn't present before. So then, when the process is reversed, and we're left with a film that exists as a mere shadow of it's former self, the effect is often so sad that no amount of music and jollity can shake off the forlorn, ill-treated aura that encompasses what's left.

Adding to it's woes, "The Life of the Party" was also caught in the aforementioned public backlash against musical films, and although never intended as a full blown musical, the axe would fall on much of what music and song the film did originally contain, most notably a dance production number set in the hotel's garden restaurant, and a comedic song entitled "You Ought to See the Horse!" presumably performed by Winnie Lightner in the race track sequence of the film. Lamentable losses, but it's a credit to the performers and director, Roy Del Ruth, that despite all this, the film holds up beautifully.

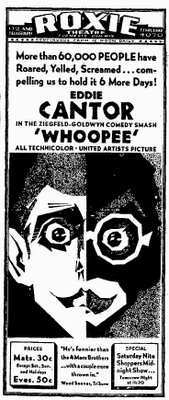

Happily, some all-talking, all-color films manage to beat the odds and survive unscathed, like the 1930 Goldwyn production of "Whoopee!," which exists today with it's visual beauty and entertainment potential undiminished --- not entirely unlike the one last marble column left standing after destruction has leveled the rest of an ancient structure we'd like to learn more of, yet can't easily without careful study and more than a bit of detective work.

In a period ad duplicated below (click to enlarge)

, there's mention of the film being in "Clear Technicolor," suggesting that it was important enough a selling point to warrant special mention, as opposed to the usual "In Technicolor" or "In Natural Colors" seen in ads for other films of the period. Indeed, another ad (pictured right), heralds a "New Technicolor Process" for the film!

, there's mention of the film being in "Clear Technicolor," suggesting that it was important enough a selling point to warrant special mention, as opposed to the usual "In Technicolor" or "In Natural Colors" seen in ads for other films of the period. Indeed, another ad (pictured right), heralds a "New Technicolor Process" for the film!

Interestingly, the ad to the left mentions three songs that do not appear in surviving prints, bringing up the question of just how complete the film we're familiar with is. It's possible that the ad was prepared by the studio while the film was still in production and they were never filmed or included to begin with, but it remains something worth investigating.

Doubtless, "Whoopee!" looked gorgeous when first screened, and it looks remarkable even today when it's let out for an infrequent airing. In the prints I've seen, at least, the film only falls somewhat short in the audio department, with the soundtrack having been so overly processed by various noise-reduction gizmo's in an attempt to erase noise artifacts that it's also lost a hefty amount of it's original fidelity along the line too.

While "Whoopee" is likely not "the greatest entertainment ever made," and Winnie Lightner's "Life of the Party" has long dimmed into near-nothingness, they're as important and priceless a document of our past as anything else to be found behind glass in a museum --- and infinitely more fun.

Audio Addendum:

While having the surface noise and hiss inherent in a vintage sound disc, here's an example of the film's original audio as recorded on disc by Goldwyn for those theaters unable or as yet unwilling to switch over to the sound-on-film process which would soon prevail. Compared to audio on circulating prints, the difference is surprising --- at least to my ears, that is.

The tune "Love Me Or Leave Me" couldn't easily be worked into the film version of "Whoopee!". A signature tune for vocalist Ruth Etting, it was originally performed on the stage in front of a drop-screen while scenery was changed behind. Simple though the setting, the tune took off and, even today, remains a standard. Here's an infrequently heard version recorded in 1929 by Allan Selby's Frascatians --- a group so named because they performed at an Oxford Street restaurant in London called "Frascati's." Simple, eh?

"Love Me Or Leave Me" (1929) The Frascatians

"Love Me Or Leave Me" (1929) The Frascatians

###

"To a man, a Widow is like finding another drink in the bottle after you thought it was empty."

Winnie Lightner, in "Life of the Party"

Winnie Lightner, in "Life of the Party"

No comments:

Post a Comment