A Variety Programme.

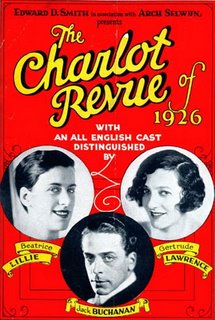

A Variety Programme.One of the nicest things--- and people, to arrive as 1925 busied itself packing to leave, was "The Charlot Revue," which played New York City's Selwyn Theater until March of 1926 --- a most respectable run for a show of this sort, that featured an "all English cast." It's really not impossible to imagine that for at least some (alright --- a few?) of those attending, it may have well been their first glimpse of a real live English variety performer, and audiences and critics alike were enchanted. That at least, is a fact.

A tune that emerged from the show which clicked almost instantly, and would be revived numerous times over the coming decades was "A Cup of Coffee, a Sandwich an You," with music by Joseph Meyer and lyrics by Irving Caesar. With starkly effective interpretation and performance by Gertrude Lawrence and Jack Buchanan, it almost seems a defining moment in 1920's musical comedy.

"A Cup of Coffee, a Sandwich and You" (1925)

Swiftly becoming a pop hit across the country, by the end of 1926 it would be given a far lusher but no less magnificent treatment by Roger Wolfe Kahn and his

Orchestra, who recorded it for Victor in December of that year.

Roger Wolfe Kahn (1926)

Blossoming in the mid 1900's and really taking off with the November 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamen's tomb, Orientalism swept the United States as all aspects of Eastern culture worked their way into architecture, design, fashion, cinema and popular music --- a trend that never completely faded nor reversed itself, as most others did.

Blossoming in the mid 1900's and really taking off with the November 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamen's tomb, Orientalism swept the United States as all aspects of Eastern culture worked their way into architecture, design, fashion, cinema and popular music --- a trend that never completely faded nor reversed itself, as most others did."Exotic" musical pieces flooded the market, many of them admittedly terrible ("Mummy Mine" comes to mind here), but some of them wonderful. "Hindustan," composed by Wallace & Weeks, is doubly wonderful as it not only neatly encapsulates the Orientalism musical trend, but is also so firmly rooted to 1918 that to listen to it is to hear, see and all but feel a warm summer's evening of that year --- preferably at a brilliantly illuminated Luna Park, with the music rising from one of the park's many bandstands, softly wafting through the sound of laughter and ocean surf.

"Hindustan" (1918) Joseph C. Smith Orchestra

By 1920, those seeking music that hearkened back to an earlier day of the "heart song" were seeing their choices quickly narrowing, as new syncopated rhythms began to replace the older and more familiar brand of recording. One notable exception arrived in March of 1920, courtesy of Columbia Records and vocalist Henry Burr, "The Rose of Washington Square." While it would be a parody version (performed by Fannie Brice among others) which would grab the brass ring and ears of listeners, I must say I was genuinely surprised when encountering the original "straight" version for the first time.

It's so sentimental, but so gently sweet a little tune that it defies all odds stacked against it from the get-go, and succeeds wildly. After all, what could be a prettier or more heartbreaking thought than a butterfly falling in love with a rose that grows, forgotten and alone, in a dim corner of a busy city park? And then, "when summer turns to autumn" --- well, it's really enough to prompt weeping at the utterly innocent and silly loveliness of it all, the sort of thing that seems to have long been torn away from life, music and art.

"Rose of Washington Square" (1920) Henry Burr

"A garden that never knew sunshine, once sheltered a

beautiful rose ---

And a butterfly gazed in to tell her one day, a story

the whole world knows ---

Rose of Washington Square, a flower so fair,

should blossom where the sun shines!

Rose, for nature did not mean that you should blush unseen, but be the queen of some fair garden!

Rose, I'll never depart! But swear in your heart,

your love to tell!

I'll bring the sunbeams from the heaven to you,

and give you kisses that sparkle with dew,

my rose of Washington Square!"

The lyrics take a sorrowful turn after this, but I'll leave you to discover precisely how (if you choose) and mention that the recording's final moments artfully incorporate a chorus of an older (and equally sentimental) tune, "Ma Blushin' Rosie."

Let's return now to the year we began this post in: 1925. A year that wasn't all gloss and frivolity by any means, it also marked what's been come to be known as "The Scopes Monkey Trial," a Tennessee event (basic details of which you're doubtless familiar) that would reverberate forever after its conclusion in July of 1925.

By October of 1925, light hearted politically minded sorts might have even danced to a musical spin on the event, and although the actual contents of the following recording has marginally little to do with anything of the trial except monkeys and Tennessee, little else was needed. A recording by the Victor Novelty Orchestra (with vocal by the always perfect Billy Murray) awaits for the eager, or merely curious.

By October of 1925, light hearted politically minded sorts might have even danced to a musical spin on the event, and although the actual contents of the following recording has marginally little to do with anything of the trial except monkeys and Tennessee, little else was needed. A recording by the Victor Novelty Orchestra (with vocal by the always perfect Billy Murray) awaits for the eager, or merely curious. "Monkey Biz-Ness Down in Tennessee" (1925)

A chimpanzee also figures into our next and final entry, although not without some difficulty in getting there!

George Jessel. "Who?" you might ask, and well you may --- while others might nod in recognition of the name. Fully deserving of vast amounts of space, I'll instead refrain by mentioning that he began a lifelong career at the age of ten by entering vaudeville, under expert tutelage of entertainment legend Gus Edwards. By 1919 he had produced his own solo show, and by 1925 he was starring in the Broadway stage version of "The Jazz Singer." The oft-repeated story is quite true. When Warners approached him with an eye towards a filmed version of the play --- but with the addition of a mechanical device known as the Vitaphone, Jessel demanded an impossibly high salary and was out, leaving the Warner Brothers to seek another stage name for the film. For better or worse, how different film history might have been!

Although his decision would haunt him for the rest of his life, in Jessel's defense, he couldn't have possibly known the electrifying effect the Vitaphone would have upon an unsuspecting cinema world, so (to quote an old song title) he's more to be pitied than censured. Doubtless, he didn't think twice when Warners called again, and after filming a silent comedy ("Private Izzy Murphy"-1926) and Vitaphone short in the studio's Brooklyn studio ("A Theatrical Booking Office"-1927) his film career was still far from spectacular.

In the article at the right, circa July of 1927, we catch a beautifully cocky George Jessel weakly pondering the inexplicable success of the Vitaphone, and seemingly completely missing the point of it at the same time.

In the article at the right, circa July of 1927, we catch a beautifully cocky George Jessel weakly pondering the inexplicable success of the Vitaphone, and seemingly completely missing the point of it at the same time."I believe the Vitaphone has about had its run," he declares. "It is so make-believe. It is impossible to make the public believe anything is real when they see the image on the screen and hear the voice coming from another part of the theater. The secret of success in the motion picture industry has been that the public believes what it sees on the screen. The Vitaphone will in time dispel such a belief."

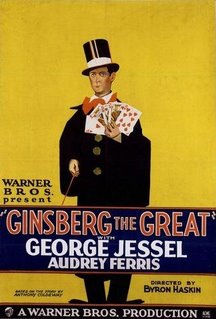

The article goes on to mention that Jessel is "now rushing work on 'Ginsberg the Great,' his second picture, so he can get back to New York for a winter stage engagement."

What the article didn't mention, and what Jessel himself may have not known at the time, was that "Ginsberg the Great" would be released four months later with a synchronized Vitaphone music and effects score for use in key theaters already wired for the sound on disc system.

With Vitaphone or without, "Ginsberg the Great" (WB-1927) was received politely but with scant attention or fanfare in most cities. Theater booking and, in turn, newspaper advertising was kept to a minimum, and when it does appear in ads, it's without mention of a soundtrack, and booked into the smallest of theaters --- second billed after a live stage performance or wee hours closing entertainment at a "Midnight New Year's Eve Frolic" in a small Midwestern theater.

With Vitaphone or without, "Ginsberg the Great" (WB-1927) was received politely but with scant attention or fanfare in most cities. Theater booking and, in turn, newspaper advertising was kept to a minimum, and when it does appear in ads, it's without mention of a soundtrack, and booked into the smallest of theaters --- second billed after a live stage performance or wee hours closing entertainment at a "Midnight New Year's Eve Frolic" in a small Midwestern theater.

No small wonder that it's a lost film then, a pity too as it really sounds quite engaging and just the sort of film that, with Langdon or Lloyd (but especially Lloyd) and with a bit of re-tooling, could have been something magnificent. Jessel plays Johnny Ginsberg, a tailor's apprentice who longs to be a great magician.

When a carnival arrives in town he leaves with it, joining the troupe as a "double" for various sideshow attractions. What Ginsberg doesn't know is that the troupe is also a traveling gang of thieves --- and that their featured attraction, a trained chimpanzee, is also a skilled pickpocket. This premise allows Ginsberg to be used as a dupe and a fall guy, and one sequence sounds especially promising: Setting their eyes on the Russian Crown Jewels (purchased by a theatrical magnate who befriends Ginsberg) as the haul of lifetime, they enlist the troupe's Oriental dancer "Sappho" (played by a perfect-for-the-role Gertrude Astor) to seduce Ginsberg and become his girl, which allows her to accompany him to the rich gentleman's home. Once inside, she gives entry to the rest of her gang --- the jewels are stolen, but Ginsberg catches on and a chase ensues with Ginsberg using ingenuity (and likely his magical devices) to capture each thief individually for the film's finale. Johnny Ginsberg is rewarded, and given a performance contract by the grateful owner of the gems.

It sounds pretty wonderful, but we'll likely never know for certain how well it all translated to the screen. Certainly not a physical comedian, nor either especially elegant or comical in appearance, the young Jessel's best features seem to have been his very expressive face --- large dark eyes, a gentle childish mouth, and a rather prominent nose. Then too, there's no getting around the fact that he was rightfully deemed an "ethnic type," which is something that didn't translate well across the country, or to be blunt, simply wasn't welcomed in all theaters.

It sounds pretty wonderful, but we'll likely never know for certain how well it all translated to the screen. Certainly not a physical comedian, nor either especially elegant or comical in appearance, the young Jessel's best features seem to have been his very expressive face --- large dark eyes, a gentle childish mouth, and a rather prominent nose. Then too, there's no getting around the fact that he was rightfully deemed an "ethnic type," which is something that didn't translate well across the country, or to be blunt, simply wasn't welcomed in all theaters.

Still and all, the combination of magic, a circus and sideshow, an expressive comedian, stolen jewels, Gertrude Astor as "Sappho" and a trained chimpanzee makes this all seem irresistible --- certainly to this writer!

In the surviving Vitaphone disc extract from "Ginsberg the Great" that closes this entry, it's fairly simple to envision the film's final scenes as the score appears to have been typically closely orchestrated to match the screen action.

The gang stealing the gems while Ginsberg entertains guests downstairs --- cymbals, coconut shells heard here. Then, using little physical effort but a lot of his magician's ingenuity, suavely knocking off the crooks one by one. Jaunty, evocative music for that. Wonderful stuff this! Popular music archaeologists will note the clever interpolation of Irving Berlin's "The Sncopated Walk" and "Discoveries" (from the Broadway revue "Watch Your Step") into the score. As melodic as it is effective? Who knows? But, let's hope --- and wait. And while we wait, we can listen:

"Ginsberg the Great" (1927) Vitaphone Disc Excerpt

###

Monkey & Man Image DN-0084029 courtesy the Chicago Daily News Collection, Chicago Historical Society

1 comment:

Needless to say, those who have an ear, as well as an eye, cocked toward WB cartoons will instantly recognize "A Cup of Coffee, A Sandwich, and You," as it was the theme Carl Stalling used to tip off a variety of food- or hunger-related themes. In a similar vein, his rival Scott Bradley at MGM would use "Sing Before Breakfast."

Post a Comment