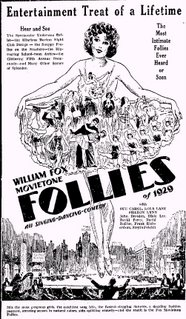

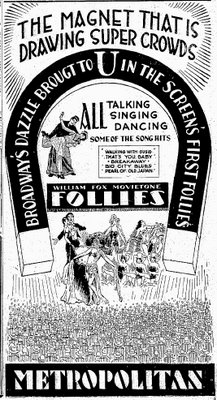

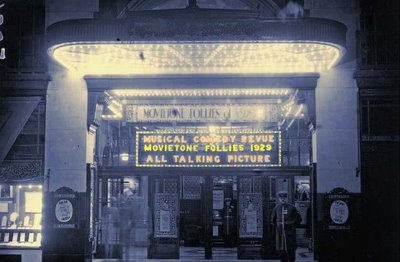

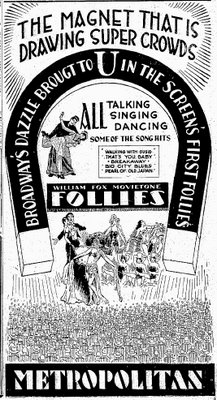

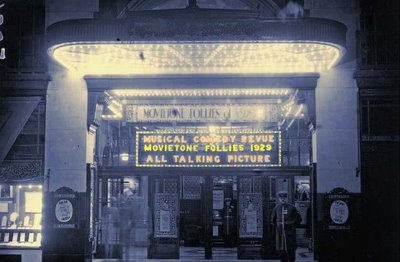

By the time it was barely eight years old, "Fox Movietone Follies of 1929," an extraordinarily popular film that was seen by hundreds of thousands of people, seemingly vanished from this earth --- completely and thoroughly.

Although countless other Fox titles were lost in a catastrophic film storage facility fire in 1937, many of these films have since been discovered elsewhere and have, in some cases almost miraculously, struggled back to life again --- aided by passionate individuals, archives and organizations around the globe. However, it appears that "Fox Movietone Follies of 1929" died a violent and rather final death in that celluloid inferno of 1937.

Indeed, it's because that the film has left so precious little of itself behind that it tends to receive perfunctory mention at best in most explorations of the early musical or sound film and, even worse, is often so poorly described and misrepresented that each new book or article further obscures and mangles the film's fleeting but brilliant life.

Despite the title, "Fox Movietone Follies of 1929" wasn't the plot-less, all-star revue film it's often thought to be. Although MGM's "Broadway Melody" (a musical with backstage sequences) would reach screens in February of 1929, the arrival of "FMF29" two months later, signalled the arrival of the first sound film to be set entirely within a theater, the first "backstage musical" in the truest sense, which played on the screen in what amounts to a "real time" format --- long before that term existed --- and similar to the way "On With the Show" (WB-1929) is also constructed.

Simply, "Fox Movietone Follies of 1929" details one hectic day and opening night of a lavish musical revue, beset with problems stemming from romantic intrigue, creditors and investors demanding satisfaction, and a spiteful leading lady and her hopeful understudy. Approximately eight reels in length, the first two reels of the film are given over to plot and character exposition, which then gives way to a series of incredibly elaborate musical revue sequences. Between these sequences, the thread of the plot is picked up and advanced, until all is well by the film's finale with personal problems solved and the success of the apparent. Yes, of course we've seen this all before --- but it should be remembered that it was done here for the first time in a sound film.

The first of the film's musical sequences, which also serves as the opening of the show-within-the-movie, presents chorus girls as the various notes of a musical scale:

"DOn't expect an opening chorus

RAise your eyes and don't ignore us!

MEdiocre shows start with them,

FOllies have a newer rhythm!

SO we have no opening chorus,

LOts of shows did that before us!

SEE dear public how we know you,

DOn't get nervous, now we'll show you!"

Attention is then turned, somehow, to the lower limbs of the musically attired chorines, who proclaim:

"Legs - Legs! We're hot for plenty of speed,

We've got the thing you need,

Legs - Legs! No face could ever replace,

A pair of beautiful legs!

Legs - Legs! Hips - Lips! Eyes - Hair!

No face could ever replace,

a beautiful pair of legs!"

Another musical sequence immediately follows, a fantasy with dress mannequins springing to life, titled "Why Can't I Be Like You?," which served to introduce Dixie Lee, who had been recently featured in the Broadway production of "Good News." (The All Movie Guide cites "The Varsity Drag" as being performed in FMF29 --- it isn't.) As described in 1929 reports of the film:

"Strolling down Fifth Avenue, she (Dixie Lee) is struck by a marvelous display of gowns on models in a modiste's window. She stops to inspect them, wondering why she never can get clothes like those she sees in the window. She sings, 'Why Can't I Be Like You?' based on this theme, and is astounded when the models come to life and parade for her inspection."

Although the song was published as sheet music, it was never commercially recorded. For that reason, the words are offered here:

"I love to window shop, I always have to stop ---

and look at beautiful ladies.

Each time that I compare

their clothes with what I wear,

It makes me sigh -- I want to cry.

Why can't I be like you, and look the way you do?

To me you always seem too lovely for words,

Lovely feathers make lovely birds,

A yard of silk and lace, add to your charm and grace.

You're in my dreams, but my dreams never come true,

Why can't I be like you?"

Four tunes from FMF29 would gain widespread popularity via radio, commercial recordings, piano rolls and printed sheet music. The first, "That's You, Baby" had a unique presentation, with the setting being a beach and seaside amusement pier --- where the tune is performed by two couples, Sharon Lynn & David Percey, and Sue Carol & David Rollins. The "double duet" effect is heightened by the camera alternately cutting between each player and each pair as the lyrics are sung. Observing all this musical romancing are two small youngsters (one of which was Jackie Cooper,) who then perform a chorus of their own before they're joined in by the two couples and then a large singing and dancing chorus. (The concept of having children singing an adult love song proved popular with audiences, and would result in it being utilized, in a nearly identical manner, for "If I Had A Talking Picture of You" in a later 1929 Fox musical, "Sunny Side Up.")

For the second musical hit from the film, "The Breakaway," the approach used here was to have the tune performed in a two contrasting but loosely connected settings. Opening with a close shot of "little colored girl" rhythmically chanting "Breakaway! Breakaway! Breakaway! Bing-bing! Dottin' yo' eye! Bing-Bing! Dottin' yo' eye! Breakaway! Breakaway!," the camera pulls back to reveal a city street setting and a large chorus. Performer Sue Carol enters, and with an exuberant cry of "Hey Kids!," that cues the orchestra, she continues:

"Hey, flappers - this way, flappers, I'll floor ya --

with a new dance, oh what a new dance,

hotter than hot, and it's got new tricks in it!

I'm fixin' it for ya, So you can learn every new turn,

Oh here is the high spot!"

The scene then switches to that of a schoolroom filled with students. A bookish professor surprises his class by suddenly piping up:

"Dear students, I'm here students ---

To make you follow this rule,

When you leave school, go out to work, and never shirk!

Take others before others can take you!

Do as you're told, 'till you grow old,

Don't break away!

Sue Carol appears on the scene again (she was apparently en route to school in the first segment,) who leads the students in a chorus. Then, as the camera moves in close on Carol, she looks directly into the camera (thereby addressing audiences in both the imaginary theater and the audience watching the film) and says:

"Hey, how would you all like to learn how to do the Breakaway? You wouldn't?

How would YOU like to learn?

Come on, come on, three times upon your heels - that's it! Come on, try it!

Aw, Daddy, come on - that's it! See? Just as easy - come on YOU try it!

You ready? You ready, Arthur?"

The "Arthur" here is Arthur Kay, as the theater's orchestra leader. He replies, "For you? Always!" and the tune is given another and final closing rendition by all, including the little girl from the opening moments of the segment who wanders in to sing a verse by herself.

At this point, we have an opportunity to get as close to "Fox Movietone Follies of 1929" as we'll ever likely be able to. A fragment of audio from the actual film's soundtrack which somehow managed to beat the odds and survive on disc --- long separated from the footage it once accompanied to theaters only equipped to handle the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system.

Here, we can listen in on a bit of plot advancement. The setting is the girls' dressing room, immediately following the conclusion of the last number, "Breakaway," (although "That's You Baby" can be faintly heard in the background scoring.) Despite everything having gone smoothly so far, the chorus girls have issues with the new owner, George Shelby --- which they lay on thick, purely for the benefit Lila Beaumont (Lola Lane) who's divided in her allegiance to George and to the show. She suddenly explodes in anger, allowing catty star of the show, Ann (Sharon Lynn) to really twist the knife. Unfortunately, George walks in during Lila's outburst and deems her as the resident troublemaker --- a fact which delights Ann, who then plays it up for all she's worth.

This is followed by one of the film's color sequences (there appears to have been at least two), a moody, elaborate tableaux /piece called "Pearl of Old Japan" that evolves into a surreal "underwater" ballet involving sunken pirate galleons and skeletons --- surely a visual feast in pastel hues! --- with the onscreen action being directed and described via vocalization (by David Percey) of the mournful lyrics:

"Pearl of Old Japan" (1929) - Soundtrack Excerpt

"There's a legend in Japan, of a maiden and her man,

He fished for pearls they say, and disappeared one day,

She's left alone to pray and plan!

Pearl of old Japan, do all you can - to find your man.

If you have a notion he's under the sea,

show him your devotion --- go under the sea!

Throw all else aside, search far and wide,

where treasures hide.

And in the wreckage of a sunken galleon,

you are sure to find your man,

poor Pearl of old Japan!"

For the third pop-music hit the film would turn out, the jaunty "Walking With Susie" is first sung by iron lunged Frank Richardson, then given a song and dance treatment by what's described as a "colored troupe," and then finally by Richardson again for the finale. How the number was staged, or in what setting, is unclear --- but given the spirited "bumpin' and thumpin'" mentioned in the lyrics, it was doubtless anything but sedate. The tune's seldom heard opening verse, as performed in the film:

"Every day I take a walk, it's Sunday.

From Monday to Sunday not one day I miss,

every little walk that I can squeeze in...

this season, it pleasin' --- the reason is this...."

"Walking With Susie" (1929) Milt Shaw & His Detroiters

At last, the plot elements --- such as they are, converge and reach a head just prior to the film's last big number. Prickly show star Ann (Sharon Lynn), is still finding things to gripe over --- in this case the simple costume for "Big City Blues," designed to depict the plain workaday outfit of any number of nameless people who find themselves alone and friendless at holiday time, in an intolerably cheerful city filled with loving families and friends. Of course, she completely misses the point and after refusing to "make a fool of myself by repeating a costume," she very nearly stops the show cold --- until a furious Lila Beaumont snatches the costume away and dons it herself before stepping out on the stage.

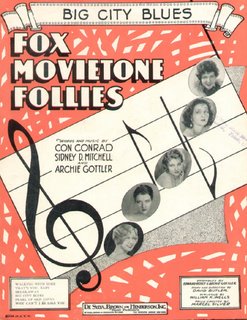

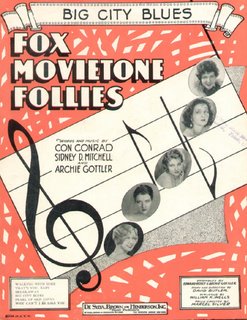

In a vast departure from preceding musical sequences, "Big City Blues" presents us with the lone pathetic figure of a woman, huddled beneath a city street lamp --- snow falling about her. The commercial 78rpm recording offered by Annette Hanshaw, is perhaps the only one out of many renditions of the tune that appears to perfectly capture the mood and tone of the piece, as well as including all of the lyrics as they appeared in the screen version. According to contemporary reports, while the song was performed, to underscore the isolation of the singer and her lament, the screen displayed "occasional flashes of joyous holiday crowds, adding tremendously to the dramatic effect." Indeed, yes!

The star's understudy, Lila Beaumont scores a hit --- just in time to allow her to join in on the show and film's big musical finale, which masterfully blended all of the film's melodies (save for "Pearl of Old Japan"!) into one sequence --- brief snatches of each song performed by those who originated them, with Lila replacing the sulking Ann, as the show concludes with full orchestra and chorus basking in thunderous applause.

As George Shelby embraces his sweetheart, he's immediately offered $55,000 for his interest in the show and he agrees, just as quickly --- and no gallant quibbles about the extra 5K profit either! Still breathless from her instant rise to stardrom, Lila has no interest in pursuing it any further and readily agrees to return with George to Virginia, provided they marry first.

The film's final view is that of Stepin Fetchit (Lincoln Perry) and a heavily accented French costume designer, concluding what was a repetitive dialogue routine that extended throughout nearly the entire length of the film --- cutting to it and away again.

I hadn't mentioned Fetchit up to this point because, quite simply, his presence in the film is comparatively small --- just one of many plain truths about the film which have been misunderstood or mangled over the years.

True, Perry's "Fetchit" character scored big with audiences and enhanced his popularity greatly, but he was by no means the film's star, as eluded to or flatly stated as truth in some published works.

Portraying the theater custodian, Fetchit's dialogue is limited to an exchange with the Shelby character in the film's opening moment, and then --- a full reel later, he exchanges a very few words with cast members of the show while delivering flowers and telegrams to their dressing rooms.

After Dixie Lee's "Why Can't I Be Like You?" number, Fetchit encounters the aforementioned French costume designer, kicking off the ballet-slipper dialogue exchange. The scene lasts for about a minute, and then resumes for roughly half that time following the "That's You Baby" sequence. Later on, when it's learned that Ann has sent a cast member for a "colored skit" or blackout, out of the theater on an errand, Fetchit is called in to fill in for him, and the skit (consisting of ten lines of spoken dialogue) ensues and ends, to be immediately followed by "Breakaway."

We return to the Frenchman and Fetchit yet again just prior to "Walking With Susie," and his character is seen again for the last time prior to the film's closing moment, in what could be termed his only featured sequence in the film --- a fleeting, peculiar and unstructured solo musical bit that's utilized (in the film) to fill stage time while difficulties with the star of the show are being ironed out. Without any title, it's described thusly in a surviving transcription of the actual film:

Cut to Stepin dancing and singing on stage:

Stepin:

"Start steppin', Stepin Fetchit,

Turn around, stop and catch it ---

Now and then if you miss it,

start again, Stepin Fetchit,

Turn again go and get it,

If they holler, Stepin Fetchit."

Cut backstage - George and creditors

Without having the ability to see the film, written transcriptions of the film's action and dialogue, newspaper reviews and accounts, still photographs, and about eight minutes of audio all add up to a miserably poor close second --- but, they do allow us, if we take the time to do so, to "see" and briefly hear the contents of a lost film that, over seventy years ago was so popular with audiences that it was booked into theaters for sometimes as many as three return engagements -- a very uncommon event to be sure.

For now, and probably forevermore, it seems that late 1930 printed advertisements for the film which declared "Final Engagement! Last Time Anywhere!" were more profoundly and sadly prophetic than anyone could have possibly imagined.

Medley - "Fox Movietone Follies of 1929"

###

In the 1929 news photo to the left, two stylish young ladies are seen pretending to listen to what was, by then, seen as a relic of another day --- the standard mechanical horn phonograph. Perched atop another dusty floor-standing talking machine, in a room strewn with suitcases, trunks and litter, the story behind the image is lost to time but the meaning is clear. In a mere slip of time, less than twenty years, a machine that would have been the pride of its owner was now a mere curiosity and ripe for ridicule at that.

In the 1929 news photo to the left, two stylish young ladies are seen pretending to listen to what was, by then, seen as a relic of another day --- the standard mechanical horn phonograph. Perched atop another dusty floor-standing talking machine, in a room strewn with suitcases, trunks and litter, the story behind the image is lost to time but the meaning is clear. In a mere slip of time, less than twenty years, a machine that would have been the pride of its owner was now a mere curiosity and ripe for ridicule at that.

The arrival of the "Double Disc" (two-sided) record came rather early in the game, although later than one might suppose, given the simple logic involved. When Columbia entered the field around late 1913, they did so with a slew of ready made advertisements filtered out to local dealers for placement in newspapers and with in-store promotional material that, in retrospect, was rather forward-thinking. If you were to wander into a music store or phonograph specialty shop, you might see a clerk dart over to the store's largest and most expensive model and within moments, you'd hear:

The arrival of the "Double Disc" (two-sided) record came rather early in the game, although later than one might suppose, given the simple logic involved. When Columbia entered the field around late 1913, they did so with a slew of ready made advertisements filtered out to local dealers for placement in newspapers and with in-store promotional material that, in retrospect, was rather forward-thinking. If you were to wander into a music store or phonograph specialty shop, you might see a clerk dart over to the store's largest and most expensive model and within moments, you'd hear:

Out of all their recordings, I think this is the most memorable. Dating from 1926, "Whaddya Say We Get Together?" is formed almost like a miniature vaudeville routine, with spoken introductions blending seamlessly into song --- and a lovely, wistful one at that.

Out of all their recordings, I think this is the most memorable. Dating from 1926, "Whaddya Say We Get Together?" is formed almost like a miniature vaudeville routine, with spoken introductions blending seamlessly into song --- and a lovely, wistful one at that.