As whatever celestial clockwork mechanism that propelled 2007 is about to wind down to a sputtering and decidedly anticlimactic halt, this lull seems an opportune time to explore items old and new --- before venturing into whatever unknown territory the new year will bring.

As whatever celestial clockwork mechanism that propelled 2007 is about to wind down to a sputtering and decidedly anticlimactic halt, this lull seems an opportune time to explore items old and new --- before venturing into whatever unknown territory the new year will bring.Enviably oblivious to life as it is in 2007, Alice White (left) is as unavoidable a presence in the realm of the early talking film as Al Jolson --- and it's rather interesting to discover that opinions of her appeal were as divided in 1929 as they are now, when she's discussed at all, that is.

In a syndicated newspaper piece dating from August of 1929, writer Dan Thomas puts it out there in a profile that could --- with little alteration -- serve adequately today to describe some of the dubious talents we inexplicably embrace today.

"How does she do it? She can't act and she's dumber than all get out! Those, and a few more things even less complimentary, have been whispered around Hollywood about Alice White for the last year. And when Hollywood folk start putting somebody on the pan, they can be brutal."

"But, while the knockers were thinking up new reports to circulate about Alice, this young actress was forging ahead until now she is one of the biggest stars on the First National lot. For a while, even the First National executives didn't hand Alice very much. In fact, they thought so little of her that they allowed her contract to expire about a year ago. Then, the exhibitors set up such a howl for more Alice White picture that she was brought back and given a new contract -- at $100 a week more than she had been getting."

"Alice has even been called high-hat. That, along with a number of other accusations, is untrue. Alice's only trouble is that she rose to stardom too rapidly. She felt that she should assume the airs of a star but she didn't know quite how to go about it. Then, directors tried to drive her and she became stubborn, thereby acquiring the reputation of being temperamental."

"If the truth were known, this blonde actress at heart is still just a kid. And once you penetrate her film star exterior, you see that kid. Until she came into pictures, Alice never knew any of the luxuries of life. As a result, once she started tasting these luxuries, she wanted to go to the very top of the cinema pinnacle so that everything she desired might be hers."

"Until recently, I was numbered among those who wondered how Alice got by. Then one day I spent the greater share of an afternoon talking to her and I knew. Film audiences penetrated her makeup --- saw the real girl, and liked her --- a thing blind Hollywood could not do."

"This youngest of stars, who three years ago was an unknown script girl, is almost pitiful in her desire to succeed. She tries so hard to do what is right that she often oversteps herself and does the wrong thing. Alice's latest film, 'Broadway Babies,' firmly established her as a star of speaking films. She couldn't dance or sing so she learned how to do both for this picture. Studio officials also wanted her to take elocution lessons, but the star showed her superior wisdom by refusing to do so."

"This youngest of stars, who three years ago was an unknown script girl, is almost pitiful in her desire to succeed. She tries so hard to do what is right that she often oversteps herself and does the wrong thing. Alice's latest film, 'Broadway Babies,' firmly established her as a star of speaking films. She couldn't dance or sing so she learned how to do both for this picture. Studio officials also wanted her to take elocution lessons, but the star showed her superior wisdom by refusing to do so.""'I don't think audiences want me to speak very correct English,' she told me. 'They want to hear me talk as any young American girl would talk, so I am going to keep right on speaking in my natural manner. I have tried to be natural in everything I do, and I think that's why fans like me. So why should I spoil it all by learning to speak correctly?'"

Sometimes, even I'm at a loss for word or waggish comment --- and at such points, music is best hurriedly brought forth.

Here are two tunes from Alice White's 1929 First National success "Broadway Babies," performed here by the California Ramblers for the Edison label, in the last days of that company's life:

"Wishing and Waiting For Love" and "Broadway Baby Dolls"

From this vantage point --- so distant to 1929, perhaps the most enjoyment that can be had in watching Alice White in her surviving early talkies is that she's so utterly unlike the vast majority of her peers. There's neither forced raucous demeanor, nor transparent attempts to appear cultured and refined that just come across as creepy --- no, she's simply herself: good, bad or indifferent. Mostly indifferent. Never seeming to quite connect with her surroundings or co-stars, or even fully understanding the lines she's speaking for that matter, Alice White defies the odds and manages to charm rather than repulse or dismay, and that's no small feat.

From this vantage point --- so distant to 1929, perhaps the most enjoyment that can be had in watching Alice White in her surviving early talkies is that she's so utterly unlike the vast majority of her peers. There's neither forced raucous demeanor, nor transparent attempts to appear cultured and refined that just come across as creepy --- no, she's simply herself: good, bad or indifferent. Mostly indifferent. Never seeming to quite connect with her surroundings or co-stars, or even fully understanding the lines she's speaking for that matter, Alice White defies the odds and manages to charm rather than repulse or dismay, and that's no small feat.One critic --- I can't recall who --- said something to the effect of "Miss White grimaces and clumsily closes one eye to give the impression she's sly and crafty, and in doing so appears to be neither."

I ain't so sure about that, folks!

Before presenting a selection of exceptionally fine tunes before moving on to our next item, it should be mentioned that many of the recordings featured in these pages can be found on what I deem to be one of the best web sites of its kind, Glen Richards' "Hot Dance and Vintage Jazz Pages," a beautifully designed, carefully documented and lovingly presented selection of music that's made to order for any of my readers. I'm including a permanent link to Glen's web site on this blog's sidebar, and gently urge you to visit. Once you do, you'll return time and again as I have.

Before presenting a selection of exceptionally fine tunes before moving on to our next item, it should be mentioned that many of the recordings featured in these pages can be found on what I deem to be one of the best web sites of its kind, Glen Richards' "Hot Dance and Vintage Jazz Pages," a beautifully designed, carefully documented and lovingly presented selection of music that's made to order for any of my readers. I'm including a permanent link to Glen's web site on this blog's sidebar, and gently urge you to visit. Once you do, you'll return time and again as I have.Edwin McEnelly and his Orchestra are up first with "Spanish Shawl," a late 1925 recording that may well prompt you to seek out those castanets you have tucked away and to do something you've never thought of doing until now.

The tune "Cryin' for the Carolines" (from 1930's "Spring is Here") has been a frequent visitor to these pages --- in renditions both awful and fine, but here's one of the best --- if not the best. Count on Johnny Marvin to put it over just right --- and dig that fiddle midway thru!

The 1929 First National Dorothy Mackaill vehicle "Children of the Ritz" may have fallen off the twig into that land of oblivion that all missing films happily if uneasily reside in --- but we have the film's theme song with us, "Some Sweet Day," and it's performed here by Bob Haring's Velvetone Orchestra precisely as it was first set down into grooves in February of 1929.

The 1929 First National Dorothy Mackaill vehicle "Children of the Ritz" may have fallen off the twig into that land of oblivion that all missing films happily if uneasily reside in --- but we have the film's theme song with us, "Some Sweet Day," and it's performed here by Bob Haring's Velvetone Orchestra precisely as it was first set down into grooves in February of 1929.Two ethereally lovely sides of a 78rpm disc by Gus Edwards & His Orchestra, dating from August of 1926, both of which pack a mighty wallop of precisely what brings you here:

"I'll Fly to Hawaii" and "Crying for the Moon"

Jack Pickford, Marilyn Miller and a pair of nervous canines are seen here aboard a steamship circa 1927 or thereabouts, and while Miller's Warner Bros. film version of "Sally" hadn't been thought of yet, we nonetheless pause a moment to revisit an old topic and, I suspect, to lay it to rest as well --- that of the seemingly absent musical number "After Business Hours," which is heralded on at least some sheet music editions for the film but which is absent from surviving prints.

Jack Pickford, Marilyn Miller and a pair of nervous canines are seen here aboard a steamship circa 1927 or thereabouts, and while Miller's Warner Bros. film version of "Sally" hadn't been thought of yet, we nonetheless pause a moment to revisit an old topic and, I suspect, to lay it to rest as well --- that of the seemingly absent musical number "After Business Hours," which is heralded on at least some sheet music editions for the film but which is absent from surviving prints.Two "Vitaphone Varieties" readers almost simultaneously wrote to point out that while the number is absent from "Sally" as a performance piece, a fragment of it survives in existing prints as incidental music in the film's elaborate background score (an oddly constructed one at that, given the fact it also makes use of "What Will I Do Without You" from "Gold Diggers of Broadway" and even Jolson's signature "I'm In the Seventh Heaven".)

Indeed, "After Business Hours" can be heard at the film's 40 minute mark, in which it serves as scoring for a throwaway bit of chorus dancing at the "Elm Tree Inn" setting and a portion of the comic business between Joe E. Brown and elderly Jack Duffy navigating his way up to his precarious seat at the club.

Clifton Webb (right, with Miller) helpfully points out that an audio fragment of "After Business Hours" as it survives in "Sally" today may be heard here, but the question still remains of course as to why a scant minute or so of music would warrant sheet music publication. My guess is that it wouldn't, and that an extended performance of the piece was either excised from prints shortly before or after the film premiered or, given the bedraggled condition of "Sally" today, the footage was simply lost somewhere between the storage shelf where the film lay for decades until what remained was thought worth saving --- even in such an imperfect format.

Clifton Webb (right, with Miller) helpfully points out that an audio fragment of "After Business Hours" as it survives in "Sally" today may be heard here, but the question still remains of course as to why a scant minute or so of music would warrant sheet music publication. My guess is that it wouldn't, and that an extended performance of the piece was either excised from prints shortly before or after the film premiered or, given the bedraggled condition of "Sally" today, the footage was simply lost somewhere between the storage shelf where the film lay for decades until what remained was thought worth saving --- even in such an imperfect format."After Business Hours" (soundtrack fragment)

Many thanks to Jessica (of San Francisco) and John R., for helping to unravel this bit of niche musical film history mystery!

A medley from the stage incarnation of "Sally," by Joseph C. Smith's Orchestra (recorded in late 1921) which artfully blends "Look For the Silver Lining,"

"Whip-Poor-Will," and "Wild Rose")

Motion Picture News described the lost 1929 Fox film "The Sin Sister" thusly: "Ill-assorted companions marooned at a trading post in the North. A small-time vaudeville dancer (Nancy Carroll) invades the frozen spaces and meets the son (Lawrence Gray) of a wealthy family who has been stranded with bad companions." While we may never know why Anders Randolph seems so upset with a bear-skin rug, or why Josephine Dunn (left) seems so ill at ease with a cigarette holder, we can lament the fact that this is just one of countless late-silent/early-sound Fox films that have vanished.

Motion Picture News described the lost 1929 Fox film "The Sin Sister" thusly: "Ill-assorted companions marooned at a trading post in the North. A small-time vaudeville dancer (Nancy Carroll) invades the frozen spaces and meets the son (Lawrence Gray) of a wealthy family who has been stranded with bad companions." While we may never know why Anders Randolph seems so upset with a bear-skin rug, or why Josephine Dunn (left) seems so ill at ease with a cigarette holder, we can lament the fact that this is just one of countless late-silent/early-sound Fox films that have vanished.To be sure, we have many a transitional period (of silence to sound) gem from that studio with us --- and some have even ventured forth out of enforced seclusion onto DVD, such as those released in conjunction with the massive "John Ford at Fox" set which arrived on the market in time for the holidays. While the full $299.99 set seems destined to serve as a corporate gift and will sit upon many an executive office's shelf, we regular folk were gifted with a fine selection of John Ford's work which may be had individually or in smaller sets. While I'm apparently one of the very few that believe that John Ford's legend far exceeds his reality, I nonetheless grabbed at the "Ford at Fox: John Ford's Silent Epics" set --- although mostly for what I consider one of the finest examples of the 1928/1929 transitional period, "Four Sons."

Inexplicably, Fox has torn away the film's original magnificent synchronized Roxy Orchestra Movietone music and effects score from "Four Sons," --- it's not even offered as an alternate audio track, and replaced it with what I feel is a very poor new one indeed. Oh, the new score sounds just fine --- clear, bright and even rich in spots, and it's a certainty that the composer studied the original Movietone soundtrack closely --- but in the end, the new score fails miserably.

Inexplicably, Fox has torn away the film's original magnificent synchronized Roxy Orchestra Movietone music and effects score from "Four Sons," --- it's not even offered as an alternate audio track, and replaced it with what I feel is a very poor new one indeed. Oh, the new score sounds just fine --- clear, bright and even rich in spots, and it's a certainty that the composer studied the original Movietone soundtrack closely --- but in the end, the new score fails miserably.The original score was so tightly interwoven into the action upon the screen that "Four Sons" never seemed so much a silent film as merely a quiet one --- with the score serving to bridge sequences, underline them, counterpoint them and highlight them so skillfully that the thought of "Four Sons" image without its' soundtrack seemed unthinkable.

The new score neatly proves not only what tremendous and lasting damage can be done to a silent film fitted out with an inappropriate score, but also how easily an early synchronized film can be transformed from a visual and aural period symphony into quite something else.

The most riveting and perhaps the defining moment of "Four Sons," when the dying pleas of a soldier on the fog shrouded battle field for his "little mother" is heard on the original Movietone soundtrack amidst almost complete silence, is shattered here by the careless and inexplicable handling in this presentation. Although we see the characters on the screen lift their heads and eyes towards the distant dying utterance, this supreme moment when the art of silent cinema co-existed beautifully with the new sound technology goes unmarked and unnoticed in the busily bland new score, turning a moment in screen history that unfailingly caused the small hairs on the back of your neck to rise into -- well, nothing. Just nothing.

The saddest aspect to all this, like much of the recent late silent and early sound product arriving on DVD, is that it always seems to just miss the mark of perfection, or always seems as though costs, effort and enthusiasm were cut or lacking in in the most ill advised spots. A million dollar image restoration and a hundred bucks spent for scoring and research, it would seem. I just don't get it. Are there no students of film history in the employ of the major studios? Someone to suggest that something isn't right --- or to boldly say "No! You'll ruin it!?" Whereas Warner Bros. (with the problematic but well intended DVD release of "The Jazz Singer) celebrates and luxuriates in their studio's contributions to the birth of the talking film, Fox --- which was as much a player in the technological leap as Warners', ignores and all but shuns it.

For films of this period being released to DVD, it's pretty much a one shot deal. No second chances --- at least in our lifetime. What lands on the store shelf BECOMES the film as it will be seen, studied, explored and understood for years and years to come. We're taking in gold and churning out tin. Not even tin --- just plastic.

A few audio fragments from the original Movietone synchronized version of "Four Sons," which now serve only as examples of what has been lost:

A few audio fragments from the original Movietone synchronized version of "Four Sons," which now serve only as examples of what has been lost:The Village Birthday Fete for the Little Mother: Here, amidst hand clapping and shouts that accompany a traditional folk dance, the audio level of the score rose and fell in volume as the image cut between the dancers and conversation between characters within the walls of a house.

The Dying Solider: (See above for description)

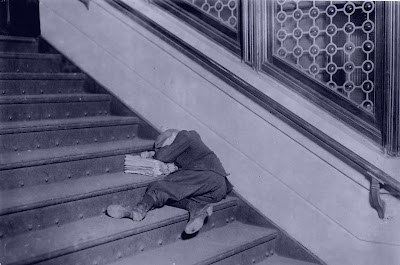

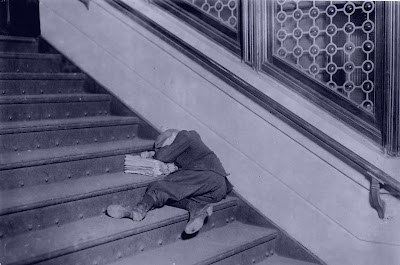

The New World & Conclusion: The Little Mother arrives in New York City and struggles to make her way to her son aboard the subway ("My New York" is used here as scoring) --- she finds herself helplessly lost on the dark, rain-slicked streets of the city. The original score interpolated bits of "The Sidewalks of New York" and "Give My Regards to Broadway" here to counterpoint the character's despair and confusion--- and, when a helpful NYC policeman comes to the woman's aid, the score reflected this (listen for "Yankee Doodle Dandy") and transformed the terrifying city landscape, by this action -- both heard and seen, into HOME for the new arrival to these shores. No such thought or care is evident in the new score and indeed, it would seem that the old woman is more lost than any of us expected, for the new score suggests she's arrived in 1948 New York instead of the city of 1928!

In the end, all this hot air on my part counts for nothing, for the damage to "Four Sons" has been done and likely won't ever be remedied. But, as cinema history is being mangled before being tossed onto the heap that is the DVD retail market, there needs to be some cautionary words spoken --- even if they sometimes can't be heard above the din of self-congratulation and back-slapping emanating from some DVD production companies.

In the end, all this hot air on my part counts for nothing, for the damage to "Four Sons" has been done and likely won't ever be remedied. But, as cinema history is being mangled before being tossed onto the heap that is the DVD retail market, there needs to be some cautionary words spoken --- even if they sometimes can't be heard above the din of self-congratulation and back-slapping emanating from some DVD production companies.We'll clear the air here --- and usher out this entry along with the old year --- with some melody, plain and simple.

Here, we have eighteen minutes of a transcribed 1929 "Brunswick Brevities" broadcast --- in which the Colonial Club Orchestra, vocalists Billy Murray and Walter Scanlan, and xylophonist Harry Brewer are featured. Among the melodies heard: "My Fate Is In Your Hands," "On the Woodpile," "Nola," "Shut the Door -- They're Coming Through the Window," "If I Can't Have You," "I'll Close My Eyes to the Rest of the World," "Nobody's Using It Now," and as announcer Norman Brokenshire hopefully suggests, "Oh, you'll recognize the rest."

See You on the Flipside of 2007! - And Thanks For Visiting!

"Auld Lang Syne" (Mechanical Music Box)

"Auld Lang Syne" (1910) - Frank C. Stanley

"Auld Lang Syne" (1931)

"Spin a Little Web of Dreams" (1933)

###

###

"Auld Lang Syne" (Mechanical Music Box)

"Auld Lang Syne" (1910) - Frank C. Stanley

"Auld Lang Syne" (1931)

"Spin a Little Web of Dreams" (1933)

###

###