If it's a remarkable feat for a musical number in an early sound film to "stop the show," then what are the chances of someone achieving the nearly impossible: stopping the show within a showstopping musical number?

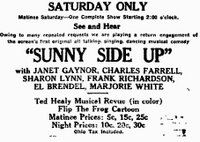

If it's a remarkable feat for a musical number in an early sound film to "stop the show," then what are the chances of someone achieving the nearly impossible: stopping the show within a showstopping musical number?Yet, that's precisely what happens during the "Turn On The Heat" production number sequence in the 1929 Fox film "Sunny Side Up" when unexpectedly, the camera cuts away from the manic jazz frenzy led by Sharon Lynn --- to focus on two of the film's auxiliary performers, Marjorie White and Frank Richardson. The pair, posing as party servants, have been standing on the sidelines watching. Richardson merely says "Listen to this," (not so much to his partner as to the film audience) and then lets loose with a rooster's crow of a vocalization that cuts through seventy-plus years of film grain, murk, damage and hiss like a machete. You almost don't want the moment to end --- it's that good, and that pure and so exhilarating --- and then you're kept waiting throughout the rest of the film to see if Richardson is given another such moment, but it never comes.

Well, actually it does -- but only as part of the "Sunny Side Up" end-credit exit music tag. Richardson isn't seen, he's just heard --- and he's not quite the strutting chanticleer here because this tune doesn't call for it, but in retrospect, Fox couldn't have left audiences who'd just seen the film with a better departing musical souvenir.

"Sunny Side Up" (1929) Exit Music Tag

Here, to the right, is an early glimpse of Frank Richardson's career on the move. It's 1923, and Richardson --- at twenty-five, has already had a career that's filled seventeen of those years. Born in Philadelphia, he'd later say he wanted to go on the stage almost as soon as he could walk and talk. Maybe so, but it wasn't until he learned to sing and developed himself into something of a boy soprano that he'd get his chance to step on a stage and exhibit the same strong presence he'd always possess. Someone took quick note, and before long the eight year old Richardson signed an engagement with Dumont's Minstrels, appearing as "The Wonder Boy Tenor."

Richardson would later join Emmet Welch's Minstrels at Atlantic City, New Jersey's Million Dollar Pier venue and then break out on his own, first with circus shows and then as master of ceremonies and entertainer in vaudeville and motion picture houses across the country.

When we next look in on Frank Richardson, in 1925, he was about to cut what he thought would be his last ties with his minstrel show lineage. Usually booking himself as "The Joy Boy of Song," he still relied heavily upon minstrel material and performance style in his act--- so much so that he sometimes billed himself as "The Ace of Spades," whenever he thought this title would have greater appeal.

When we next look in on Frank Richardson, in 1925, he was about to cut what he thought would be his last ties with his minstrel show lineage. Usually booking himself as "The Joy Boy of Song," he still relied heavily upon minstrel material and performance style in his act--- so much so that he sometimes billed himself as "The Ace of Spades," whenever he thought this title would have greater appeal.By late 1926 though, his "Ace of Spades" persona was ready to be buried once and for all. According to a publicity placement likely composed and distributed by Richardson himself to newspapers in towns he was booked into: "Frank Richardson, the Joy Boy of Song, is no longer a blackface comedian. He will sing his songs 'natural,' which is the vaudeville slang for whiteface. One day Mr. Richardson, because of a delayed railroad schedule, reached a theatre where he was to play too late to make up. He went on in street clothes without the customary burnt cork. His act went better than it had ever gone before. Then and there he ceased to be a blackface comedian. In calling himself the Joy Boy of Song, Mr. Richardson merely announces that he is a singing comedian of a different type with individuality."

Richardson's "Ace of Spades" persona might have been buried then and there, but he little suspected it would come calling again, in less than four years time, and that he'd be donning the customary burnt cork for an entertainment medium that would present him to more people in more audiences in just a few weeks than he had ever played before in half a lifetime of show business.

Unfortunately, we currently have no way of knowing what Frank Richardson's debut performance in "Fox Movietone Follies of 1929" looked or sounded like, but he couldn't have been given a better tune, the cheeky "Walking With Susie," just right for the strutting, cocksure Richardson's barrel-chested ringing voice and demeanor.

Unfortunately, we currently have no way of knowing what Frank Richardson's debut performance in "Fox Movietone Follies of 1929" looked or sounded like, but he couldn't have been given a better tune, the cheeky "Walking With Susie," just right for the strutting, cocksure Richardson's barrel-chested ringing voice and demeanor.In "Sunny Side Up," he's given more to say than he's given to sing --- but he pulls it off, and in a role (that of a braggart ham) that could just as easily prompt audience dislike as much as acceptance, he wins the day --- largely because he's an endearing, gentle sort of braggart ham who, the viewer feels sure, probably believes less in his boasts than anyone else. Interestingly, it's the secondary roles in "Sunny Side Up," enacted by Richardson, White and Lynn that linger long after Gaynor & Farrell's sticky affectation wears off. As for El Brendel, well.... that's something else entirely!

The fact remains that "Sunny Side Up," was and is a remarkable film that impressed audiences so upon its original release that it was only one of very, very few early sound films that would be revived, most of them musicals incidentally --- by popular demand --- well after its premiere, in this case well into the last months of 1933.

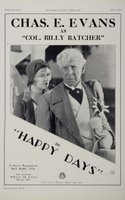

The fact remains that "Sunny Side Up," was and is a remarkable film that impressed audiences so upon its original release that it was only one of very, very few early sound films that would be revived, most of them musicals incidentally --- by popular demand --- well after its premiere, in this case well into the last months of 1933.Richardson's first two successes proved a hard act to follow, although he'd briefly have a chance to shine again in Fox's minstrel-themed "Happy Days," where he's billed and presented as himself, singing the infinitely catchy tune "Mona." How Richardson and his highly recognizable voice eluded the phonograph companies is any one's guess, so while we don't have a 78rpm commercial recording of his performance, I offer the two next best things. First, an extract of Richardson's performance from the film "Happy Days" itself, and then George Olsen's equally fine commercial rendition of the same tune, released late in 1929 on Victor Records with Fran Frey providing the warbling in lieu of Richardson.

"Mona" (1930) Frank Richardson

"Mona" (1930) George Olsen & His Music

Following "Happy Days," Richardson would still have one more film appearance to put in before he could finally cast off and bury his "Ace of Spades" persona, although after he did just that, following end of work on "New Movietone Follies of 1930," his film career would evaporate along with it --- an irony that couldn't have escaped him entirely.

###