"Before the picture business went talkie," said actress Betty Compson in late 1929, "its players seldom gave a great deal of study to their roles. They arrived at the studio in the morning, made up and went on the set."

"Before the picture business went talkie," said actress Betty Compson in late 1929, "its players seldom gave a great deal of study to their roles. They arrived at the studio in the morning, made up and went on the set.""There, a director told them to walk through a door and appear startled. They seldom had occasion to know why they were startled, who was startling them, or what they were to do next."

"The talkies have changed all this. The weeks of rehearsal before the picture goes before the cameras, attentive study of lines, and a full knowledge of the story tends to get the player more into his part than the silent film ever did. The result is better acting, better characterizations and a more convincing story."

In mid-December of 1928, Hollywood columnist Dan Thomas had this to say of Compson's first talking picture, "The Barker," --- a part talking First National Vitaphone feature that, while having survived --- remains peculiarly elusive --- in a piece titled "The Talkie Is Improving":

"A talking picture which really is worth seeing. That was my reaction to 'The Barker,' which has just opened in Hollywood. I would rank 'The Barker' next to Jolson's 'The Singing Fool' in the way of talking screen entertainment -- and it's way, way above other 'squawkies' which have been dumped on the market these last few months. "

"'The Barker,' a story of a carnival troupe, was made first as a silent picture. Then when Warner Brothers bought First National, portions of the film were remade with talking sequences. And strangely enough, the dialogue actually added to the entertainment value of the production."

"If Hollywood's great film factories would turn out more talkies like 'The Barker,' dialogue would be almost a cinch to become a permanent fixture in the movie racket. As it is -- well, let's wait until the novelty wears off and see what happens."

Publicity material for "The Barker" allows us a glimpse at a film we can't easily experience otherwise:

"The story of 'The Barker' concerns Nifty Miller (Milton Sills,) barker for a street carnival, who's young son Chris (Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.) comes to visit him. Nifty leaves off cursing and drinking and 'gives the air' to the Hawaiian dancer (Betty Compson) with whom he has been living. In a fit of revenge she induces Lou (Dorothy Mackaill,) a show girl of easy virtue, to capture the affections of Nifty's son. They fall in love and leave the carnival to get married. Nifty becomes disgusted and goes off on a toot, leaving the show flat."

"Some days later, in a town where the troupe is showing to small business, Lou and Chris turn up. The Hula dancer is running a doll concession with small results and a weak barker. Suddenly, Nifty shows up and listens to his successor with disgust. He starts to reorganize and among other things learns that Chris is studying law in the office of an attorney, and is happy once more."

"Some days later, in a town where the troupe is showing to small business, Lou and Chris turn up. The Hula dancer is running a doll concession with small results and a weak barker. Suddenly, Nifty shows up and listens to his successor with disgust. He starts to reorganize and among other things learns that Chris is studying law in the office of an attorney, and is happy once more.""The spiel of the barker before the tent of the Hawaiian dancer, the dialogue in the big scene where Nifty learns that the dancer is responsible for Chris' decision to marry Lou, the sounds of the fight between the carnival people and the villagers are given with such realism that one seems to be watching the actual flesh-and-blood characters."

Despite this glowing recommendation, whoever wrote the copy for the uniformly wonderful Lima, Ohio "Sigma" theater ads of the period found himself utterly stumped -- and says as much -- in the ad at the left, from December of 1928. But, he gathered himself enough to point out that audiences will Hear and Understand the players --- and that "over half the picture" was "synchronized with clear, concise talking sequences" --- which is more than can be said for some recent films I've viewed that would have benefited from closed captioning.

Fans of Dorothy Mackaill, Fairbanks the Junior and Milton Sills (?) notwithstanding, I lament not having ever seen and heard Betty Compson in her first appearance on the talking screen --- for I tend to think she'd have come off the best among her fellow players in the new medium, playing a role she had enacted many times before and would many times again. Actually, that's not entirely true. What I mean is that Betty Compson was --- almost always --- pretty much Betty Compson. Oh, she'd trot out an accent now and again, or affect an upper class mode of speech, but that brittle yet somehow melodic whip-crack of a voice she possessed always reigned supreme. No matter what the scenario or role, she always seemed ready to say something particularly stinging, or conclude even the most florid and impassioned of speeches with "ya get me?"

Fans of Dorothy Mackaill, Fairbanks the Junior and Milton Sills (?) notwithstanding, I lament not having ever seen and heard Betty Compson in her first appearance on the talking screen --- for I tend to think she'd have come off the best among her fellow players in the new medium, playing a role she had enacted many times before and would many times again. Actually, that's not entirely true. What I mean is that Betty Compson was --- almost always --- pretty much Betty Compson. Oh, she'd trot out an accent now and again, or affect an upper class mode of speech, but that brittle yet somehow melodic whip-crack of a voice she possessed always reigned supreme. No matter what the scenario or role, she always seemed ready to say something particularly stinging, or conclude even the most florid and impassioned of speeches with "ya get me?"Here's a ripe bit of faux-elegant Compson from the 1929 First National film "The Time, the Place and the Girl" (Compson and co-star Grant Withers can be seen in a still from this film at the head of this post) --- an all-talkie which is now presumed to be lost, leaving behind only its audio.

In the first excerpt, Compson --- wealthy wife of a crooked investment banker --- is confronted by her husband (John Davidson) for nurturing what he deems a possibly disastrous relationship with the young college chump (Grant Withers) he hand picked to be his fall-guy in a phony stock scam.

In the first excerpt, Compson --- wealthy wife of a crooked investment banker --- is confronted by her husband (John Davidson) for nurturing what he deems a possibly disastrous relationship with the young college chump (Grant Withers) he hand picked to be his fall-guy in a phony stock scam."The Time, the Place and the Girl" (1929) - Excerpt 1

Withers discovers her husband's scheme, unloads the stock on Compson, and makes tracks for the coast with his girlfriend. Here, in the concluding moments of the film (which includes the picture's exit music --- "Honey Moon," by Joseph K. Howard) Compson and husband realize they've been had --- and how!

"The Time, the Place and the Girl" (1929) - Excerpt 2

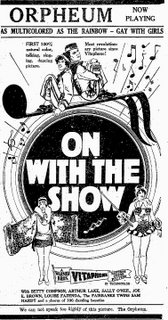

If it can be supposed that Compson ever had a supreme moment on film --- an odd notion in of itself --- then surely it was in the role of Nita French, the aging and prickly star of "The Phantom Sweetheart" in the 1929 Warner Bros. all-Technicolor musical "On With the Show."

Helped along by a dialogue script that reads like a slang dictionary and a wonderful assortment of stock players elevated to leading roles, Compson shines as never before (and never would again.) The combination of the pastel-hued photography, a lush wall-to-wall incidental musical score and a clutch of memorable tunes all must have made this quite the special event for movie-goers in 1929 --- the merest hint of which can still be palpably felt while watching the ragged B&W print that managed to stagger through the decades and collapse at our feet today.

Helped along by a dialogue script that reads like a slang dictionary and a wonderful assortment of stock players elevated to leading roles, Compson shines as never before (and never would again.) The combination of the pastel-hued photography, a lush wall-to-wall incidental musical score and a clutch of memorable tunes all must have made this quite the special event for movie-goers in 1929 --- the merest hint of which can still be palpably felt while watching the ragged B&W print that managed to stagger through the decades and collapse at our feet today.Two excerpts from "On With the Show." In the first, Compson suspects the theater manager has snatched the payroll and tagged it a heist --- and refuses to go on: "On With the Show" (1929) - Excerpt 1

As the film concludes, Compson's role has been taken over by Sally O'Neill --- and Betty realizes it's time to pack it in once and for all and face an uncertain future like the trouper she is.

"On With the Show" (1929) - Excerpt 2

An Oddity:

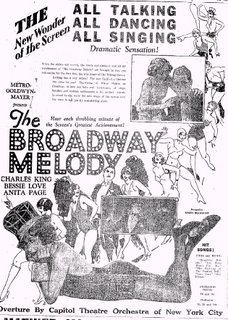

An Oddity:"'The Broadway Melody,' which came to the Capitol Theater last night is one of the best-looking and most entertaining films which has come this way for a long time. And Bessie Love, who is destined to become famous again, after a period of neglect by the powers that be in the film industry, gives the most

exciting performance that the talking pictures have yet recorded. She has a fine, deep voice which matches perfectly her odd charm of manner and pretty face. Anita Page, a comparative newcomer to the screen, and a lovely and intense lady of the best blonde coloring, if we may judge from the Technicolor sequence, supports Miss Love."

Have we been mistaken all these many years in thinking that "The Wedding of the Painted Doll" was the film's one color sequence when, in fact --- if this review is accurate --- it suggests that color was limited to the "Love Boat" tableaux?

Norma Terris and J. Harold Murray pose oh-so-prettily in this shot from the largely lost Fox Movietone 1929 musical "Married In Hollywood." (At least a portion of the film's concluding color reel survives, and has been trotted out for a fortunate few at sporadic archive screenings.) For those gathered here, we have the photo to look at --- and two wonderful melodies from the film to listen to, as performed by Louis Katzman's Brunswick Orchestra:

Norma Terris and J. Harold Murray pose oh-so-prettily in this shot from the largely lost Fox Movietone 1929 musical "Married In Hollywood." (At least a portion of the film's concluding color reel survives, and has been trotted out for a fortunate few at sporadic archive screenings.) For those gathered here, we have the photo to look at --- and two wonderful melodies from the film to listen to, as performed by Louis Katzman's Brunswick Orchestra:"Dance Away the Night" (1929)

"Peasant Love Song" (1929)

From a June 1930 newspaper profile of phonograph and radio vocalist Frank Munn:

From a June 1930 newspaper profile of phonograph and radio vocalist Frank Munn:"Life is full of striking paradoxes, and the radio world is as full of them as the more truly mundane spheres. Frank Munn, for example, who is known to the air as Paul Oliver, never knew his own mother -- despite the fact that his ballads dedicated to 'Mother' have endeared him to millions."

"The urge to express his soul in song was present during his entire childhood in the Bronx, New York, where he was born. After five years in a factory, when he was 25 years old, his friends prevailed upon him to give up his work and take singing lessons. Therefore, Frank changed from the largely manual labor of sharing in the manufacturing of turbines to the labor of singing scales."

"Two years brought him a contract with a phonograph company and financial reward. The 'exclusive artist' clause, however, kept him from broadcasting until he got a new contract in 1928. Having played center on his High School football team, sports have a personal interest for him. Chick Meehan, the well-known New York University coach, is among his intimates who call him both Frank and Paul, upon different occasions. Though he admires operatic music, he not only prefers the simple ballads he sings, but realizes they are better suited to his voice. Besides, when he sings them with his hand on his heart and all the feeling in his being, he lifts them to a higher level."

Indeed. Here's Mr. Munn lifting two melodies of the early synchronized film era to the heavens, where they likely still cling and reverberate brightly:

Indeed. Here's Mr. Munn lifting two melodies of the early synchronized film era to the heavens, where they likely still cling and reverberate brightly:"Lady Divine" (1928)

Theme Song of "The Divine Lady" (First National)

"When Love Comes Stealing" (1928)

As Featured in "The Man Who Laughs" (Universal)

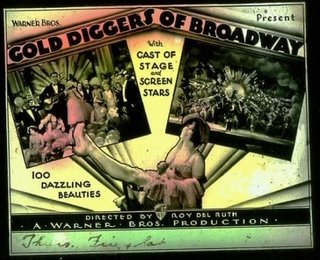

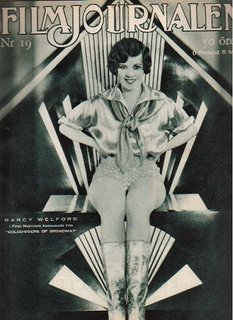

A trio of memorable melodies --- although receiving scant attention by phonograph companies swamped with material begging release in 1929 and 1930:

"Go To Bed" (1929) Eugene Ormandy & His Orchestra

From "Gold Diggers of Broadway" (Warner Bros.)

"I'll Still Belong To You" (1930) Leonard Joy's Orchestra

From "Whoopee!" (Goldwyn)

"Dust" (1930) The High Hatters

From "Children of Pleasure" (Metro)

It's always a pleasure to welcome back vocalist Franklyn Baur to these pages, and this time he returns with two melodies that present his voice in two decidedly different forms.

It's always a pleasure to welcome back vocalist Franklyn Baur to these pages, and this time he returns with two melodies that present his voice in two decidedly different forms.In 1927's "Calling," (with Roger Wolfe Kahn's orchestra,) Baur is in top form --- light, silvery voiced and lyrical.

In 1929's theme from Paramount's "The Cocoanuts," the timbre of Baur's voice is richer, more robust --- but somehow sadder and quite without the infectious spark apparent in the earlier rendition.

"Calling" (1927) Roger Wolfe Kahn & His Orchestra

Vocal by Franklyn Baur

"When My Dreams Come True" (1929) Franklyn Baur

From "The Cocoanuts" (Paramount)

We pause now for a personal message from William Fox, President of the Fox Film Corporation, from March of 1929:

"Gone are the days when talking pictures could hope to succeed on novelty alone. The talking picture has reached maturity -- its infant days are over. The public has a right to expect talking pictures of the same high quality as the outstanding successes of the fast-fading silent screen -- classics like 'The Birth of a Nation,' 'The Covered Wagon,' and 'Street Angel.'"

"Fox Films has achieved that goal. Fox Movietone, first in sound on film, now sounds the last word in talking pictures with 'In Old Arizona,' to be presented for the first time at the (INSERT THEATER NAME HERE.)"

"It represents the culmination of five years of perfecting talking film and twenty-five years of producing motion pictures. It represents the combined genius of two directors -- Raoul Walsh and Irving Cummings. It brings to you for the first time the voices of such screen favorites as Warner Baxter and Edmund Lowe, the unforgettable Sergeant Quirt of 'What Price Glory,' and Dorothy Burgess, star of many Broadway productions."

"What is it that makes 'In Old Arizona' so different from other talking pictures? First, the fact that it was made on location, actually screened in the open amid the natural splendors of the southwest. Previously, dialogue had to be recorded in sound-proof studios. But the Fox Movietone process (photographing sound on film) not only caught and reproduced with fidelity the voices of the actors in 'In Old Arizona' but actually filmed and reproduced the natural sounds of the outdoors: the whining of the wind, the braying of mules, the rustle of leaves. Thus, the techniques of the stage and screen have been combined in perfect harmony, the first time this has ever been accomplished."

"What is it that makes 'In Old Arizona' so different from other talking pictures? First, the fact that it was made on location, actually screened in the open amid the natural splendors of the southwest. Previously, dialogue had to be recorded in sound-proof studios. But the Fox Movietone process (photographing sound on film) not only caught and reproduced with fidelity the voices of the actors in 'In Old Arizona' but actually filmed and reproduced the natural sounds of the outdoors: the whining of the wind, the braying of mules, the rustle of leaves. Thus, the techniques of the stage and screen have been combined in perfect harmony, the first time this has ever been accomplished.""Against this perfect background is unfolded a swift-moving action-full romance of frontier days, told entirely in dialogue -- intelligently written and perfectly recorded. Every word of it comes to you as clear and natural as life itself."

"'In Old Arizona' has been pre-shown in Los Angeles, Portland and Seattle. In all three cities, it played to the biggest box-office receipts in the history of the theaters. In all three cities, the critics unanimously acclaimed it the last word in talking pictures."

"Seeing and hearing is believing. Come to the (INSERT THEATER NAME HERE) and see and hear it for yourself."

If that doesn't induce you to seek out the top-notch DVD of "In Old Arizona" that Fox unceremoniously tossed on the market some time back (with what looks to be Paint Shop Pro clip-art packaging design) then perhaps James Melton's soul-stirring rendition of the film's theme song might...

If that doesn't induce you to seek out the top-notch DVD of "In Old Arizona" that Fox unceremoniously tossed on the market some time back (with what looks to be Paint Shop Pro clip-art packaging design) then perhaps James Melton's soul-stirring rendition of the film's theme song might..."My Tonia" (1929) James Melton

Theme Song of "In Old Arizona"

While we have Mr. Melton with us, perhaps we can persuade him to --- oh! No need, he hasn't budged from that microphone:

"Chant of the Jungle" (1929)

Theme Song of "Untamed" (Metro)

"Beautiful Love" (1931)

As Featured in "The Mummy" (Universal)

In early December of 1929, Chester Bahn, Dramatic Critic of the Syracuse Herald, had a surprisingly cozy and informative chat with his readers about Technicolor films:

"And today, ladies and gentlemen, let us take stock, checking the forecast set down in this column on another Sabbath morn in the good old summertime -- a forecast which was, in the lingo of newspaper craft, bannered 'Pictures In Natural Colors Will Feature Next Year's Production.'"

"This is no clinical discourse, but a serious attempt to weigh the accuracy of a prediction plus the seasonal announcements of Hollywood's major producers. As evidence of its timeliness, let me merely refer to the recent six weeks' run of 'Gold Diggers of Broadway' and employment of color in other past, present and future local film bookings."

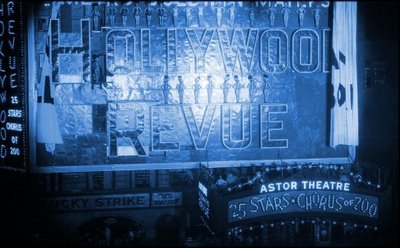

"At the moment, color is used effectively in Irene Bordoni's 'Paris' at the Strand, and less so in 'Glorifying the American Girl' at the Paramount. Pictures with color already shown included 'Broadway Melody,' 'Fox Movietone Follies,' 'The Hollywood Revue,' 'Married in Hollywood,' 'The Desert Song,' 'On With the Show,' and 'Rio Rita.' On the immediate horizon, there is 'Broadway' Eckel-theater bound."

"And this, my friends, is just the beginning. Technicolor, Inc. which controls the process now in vogue, advises that 14 features entirely or partly in natural color have been completed and that it is expected the principal studios will make a total of 50. Eleven actually are in the making. Monroe Lathrop, Hollywood columnist, is authority for the statement that before this time next year, 109 productions will be shown in color -- wholly or in part."

"And this, my friends, is just the beginning. Technicolor, Inc. which controls the process now in vogue, advises that 14 features entirely or partly in natural color have been completed and that it is expected the principal studios will make a total of 50. Eleven actually are in the making. Monroe Lathrop, Hollywood columnist, is authority for the statement that before this time next year, 109 productions will be shown in color -- wholly or in part.""The number of Technicolor specials to be released by Warners during this season of 1929-30 totals eight. This means that more than one-fifth of their entire schedule of 35 Vitaphone productions for the current year are utilizing Technicolor."

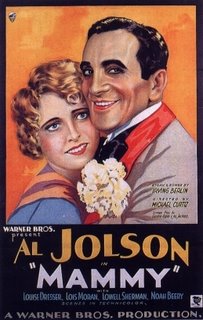

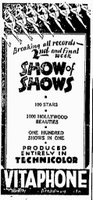

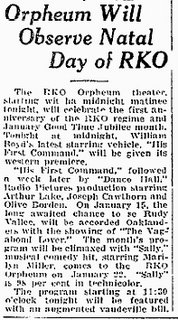

"The productions in color or with color sequences that are headed for Syracuse include 'Cotton and Silk' (note- working title for "It's A Great Life",) 'Golden Dawn,' 'General Crack,' 'Pointed Heels,' 'Sally,' 'Show of Shows,' 'Son of the Gods,' 'The Vagabond King,' 'The Rogue Song,' 'Under a Texas Moon,' 'Hold Everything' and Al Jolson's next picture, 'Mammy.'"

"Other color features now on the way include 'Devil May Care,' 'Lord Byron of Broadway,' 'Happy Days,' 'Dixiana,' 'Show Girl in Hollywood,' 'Song of the Flame,' 'Lady in Ermine,' 'Bright Lights' and 'Paramount on Parade.'"

"And, augmenting that list are these: 'Cameo Kirby,' 'New Orleans Frolic,' 'King of Jazz,' 'Bride of the Regiment,' 'Dance of Life,' 'Hell's Angels,' 'Hit The Deck,' 'Mamba,' 'Melody Man,' 'Mysterious Island,' 'No No Nannette,' 'Peacock Alley,' 'Puttin' on the Ritz,' 'Radio Revels' and 'The Viking.'"

"And, augmenting that list are these: 'Cameo Kirby,' 'New Orleans Frolic,' 'King of Jazz,' 'Bride of the Regiment,' 'Dance of Life,' 'Hell's Angels,' 'Hit The Deck,' 'Mamba,' 'Melody Man,' 'Mysterious Island,' 'No No Nannette,' 'Peacock Alley,' 'Puttin' on the Ritz,' 'Radio Revels' and 'The Viking.'""At present, there are 34 Technicolor cameras in the movie colony, and those are being augmented at the rate of one a week. But since all are working night and day shifts, they really are doing the work of 68 cameras. When the producers definitely turned to color eight months ago as the result of the success of 'On With the Show,' there were only eight Technicolor cameras in operation. Since that time, Technicolor has increased its working capacity eight times in an effort to meet the demand for color."

"Hollywood itself is sold on natural color pictures, and while undoubtedly the first rush may be attributed to that ever-raging film malady, copycat-itis, the conversion actually has keen appreciation of the possibilities behind it. Which is scarcely surprising. It is not so long ago that the less alert moguls had a painful lesson when the cinema found its voice. You remember those superior comments that sound could never, never, usurp the place of the silent picture, of course!"

"Stars of five principals studios were asked for their opinions on Technicolor after having worked with it. Al Jolson, Dennis King, Bebe Daniels, Lawrence Tibbett and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. were among those who replied, each citing a distinct advantage which color photography brings to the cinema."

"Jolson declared that Technicolor gives an illusion of the much sought third dimension. He said: 'In a remarkable way, it gives the semblance of third dimension to a picture, without its deformities -- a combination that experts have been seeking and that we have been hoping they'd develop. No longer do we have to judge the distance an object in a picture is from us by its size alone.'"

"Jolson declared that Technicolor gives an illusion of the much sought third dimension. He said: 'In a remarkable way, it gives the semblance of third dimension to a picture, without its deformities -- a combination that experts have been seeking and that we have been hoping they'd develop. No longer do we have to judge the distance an object in a picture is from us by its size alone.'""Dennis King asserts that Technicolor enhances virility of action more than black and white photography: 'I entered a projection room in fear and trembling to see my first tests in color. I came out a convert. My work in 'The Vagabond King' convinced me that color, instead of killing virility, develops that quantity.'"

"Lawrence Tibbett, the Metropolitan Opera star, back in New York after completing his first film, 'The Rogue Song' for Metro-Goldwyn-Mater, contributes this: 'Color and music are inseparable when it comes to entertainment. You can't produce opera without clothing your singers in colorful costumes and I think that it will be found that one can't produce satisfactory musical entertainment in sound pictures without using color photography. One thing, however, spoils my interest in Technicolor at the present day. This is the fact that so many producers try to combine Technicolor scenes with scenes filmed in black and white. To my mind this is impossible. The moment the color photography ceases and the black and white scenes are shown, the picture drops several degrees in interest.' And to that opinion, I add a hearty 'Amen!'"

Careless printing of Technicolor elements --- the result of a glut of product demanding release --- would turn a process once deemed enchanting by critics and audiences alike into something akin to an unwelcome guest by the end of 1930, as audiences reached the saturation point in both musicals and eye straining pastel hued grain and blur.

Careless printing of Technicolor elements --- the result of a glut of product demanding release --- would turn a process once deemed enchanting by critics and audiences alike into something akin to an unwelcome guest by the end of 1930, as audiences reached the saturation point in both musicals and eye straining pastel hued grain and blur.When it was all too much, there was --- as there always had been, the radio. But even there, the trend for musical films was impossible to escape entirely.

Recorded advertisements, studio sponsored broadcasts, abridged versions of film scores --- and even more than a few examples of film soundtracks being piped out of the theater and into radio studios for re-broadcast to lure anyone who might still be at home (listening to free radio) into a theater and past the ticket booth --- all made it difficult to ignore and, in effect, also likely aided in the swift about-face the public gave the musical film.

As noted in these pages numerous times, the survival rate of transcriptions of radio product from this period is even worse than many of the films they promoted and, in typical irony, what does survive is invariably dull or wholly unmemorable.

As noted in these pages numerous times, the survival rate of transcriptions of radio product from this period is even worse than many of the films they promoted and, in typical irony, what does survive is invariably dull or wholly unmemorable.There are exceptions of course, and here's just such an example --- a presumed "remote" broadcast of Ben Pollack & His Band from mid-summer of 1930. In this musical program, two Paramount films are plugged via sprightly performance of the tunes they featured: the title tune of "Let's Go Native" and "My Future Just Passed" from "Safety In Numbers." Other melodies featured in this broadcast include "So Beats My Heart For You," "How Are You Tonight In Hawaii?," "Blue is the Night," "I'm Confessing That I Love You," "Ragging the Scales," and "Betty Co-Ed." Enjoy!

Ben Pollack - Summer of 1930

And, while unlikely to figure anywhere else within these pages, here's vocalist Kate Smith's 1932 recording "A Memory Program," in which she presents a medley of sentimental ballads on the brink of falling from fashion and our collective memory, seemingly forever.

These "orphaned" melodies are always given haven here --- where, among kith and kin, they can once again find appreciative --- or at least, curious, listeners.

These "orphaned" melodies are always given haven here --- where, among kith and kin, they can once again find appreciative --- or at least, curious, listeners.Vocalist Olive Kline (left) steps forth from the shadows of mid-1921 to once again offer: "The Japanese Sandman" (1921)

And, Henry Burr (below right) gives us a stirring 1925 rendition of the turn of the century melodic cornerstone, "After the Ball." While the orchestration has been tweaked a bit, Burr's voice still rings of 1892 --- and elevates the recording from the mundane to the priceless.

Charles Kaley, stage, radio, recording artist and star of Metro's 1929 "Lord Byron of Broadway" was featured in an earlier post that can be found via this link, but here's Mr. Kaley's two recordings of melodies from that peculiar and much underrated film:

Charles Kaley, stage, radio, recording artist and star of Metro's 1929 "Lord Byron of Broadway" was featured in an earlier post that can be found via this link, but here's Mr. Kaley's two recordings of melodies from that peculiar and much underrated film:"Should I?" (1929) and

"A Bundle of Old Love Letters" (1929)

It's interesting to note that Kaley's voice fares far better here than it does in the film. The playful, somewhat inventive phrasing heard here indicates that the performer's full (vocal) potential was never fully utilized in a film that surely could have used a bit of cheer.

We'll conclude this entry with a gallery of visual and musical offerings --- of no particular connection to one another other than the obvious. Look! Listen!! Enjoy!!!

"I'm Doing What I'm Doing For Love" (1929) - From "Honky Tonk"

"I'm Doing What I'm Doing For Love" (1929) - From "Honky Tonk"The Teddy Kline Orchestra - Vocal by The Two Jazzers

"He's A Good Man To Have Around" - From "Honky Tonk" (1929)

"He's A Good Man To Have Around" - From "Honky Tonk" (1929)Sophie Tucker & Orchestra

"I'm Just a Vagabond Lover" - From "The Vagabond Lover" (1929)

Harry Salter & His Orchestra

"It Seems to Be Spring" - From "Let's Go Native" (1930)

"It Seems to Be Spring" - From "Let's Go Native" (1930)Joe & Dan Mooney, The Sunshine Boys

"Rio Rita" (1927) - From The Ziegfeld Production

The Bob Haring Society Nightclub Orchestra

"Sweetheart We Need Each Other" - From "Rio Rita" (1929)

Ben Pollack & His Park Central Orchestra

"Chant of the Jungle" - From "Untamed" (1929)

James Melton & Orchestra

"Tip Toe Thru the Tulips" - From "Gold Diggers of Broadway" (1929)

Fred Rich's Rhythmicians, vocal by The Two Jazzers

"Were You Just Pretending?" - From "No, No Nanette" (1930)

James Melton & Orchestra

"The Whip" - From "Golden Dawn" (1930)

Noah Beery & the Vitaphone Orchestra

The Blue Coal Minstrels (1931)

Featuring Al Bernard (Above)

"When Day Is Done" (1926)

The Indiana Hotel Broadcasters

More Drama Than a Ten Chapter Serial Play - Salt Lake City, Utah - 10 April 1929

###

###