It's Christmas of 1930, and self-proclaimed "Broadway's Bad Boy" (which he alternates with "Broadway's Playboy") Jack Osterman, appears to be riding high.

The Vitaphone short subject he filmed in Warner Brothers' Brooklyn, New York studio in late 1929 was winding down a successful run in theaters across the country, where it accompanied the All-Technicolor feature "Song of the Flame," and there was even talk of Osterman doing his own feature for Columbia, with a story penned expressly for him by no less a personage than Eddie Cantor.

The Vitaphone short subject he filmed in Warner Brothers' Brooklyn, New York studio in late 1929 was winding down a successful run in theaters across the country, where it accompanied the All-Technicolor feature "Song of the Flame," and there was even talk of Osterman doing his own feature for Columbia, with a story penned expressly for him by no less a personage than Eddie Cantor.

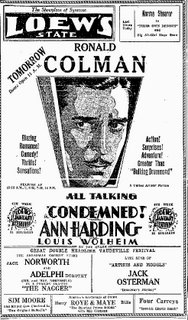

For now though, there was a brief holiday lay-off to enjoy, and then it was off to a frigid Syracuse, New York to fulfill a booking with the Loew's circuit, where he'd be on the same bill with old-timer Jack Norworth (former partner of Nora Bayes), putting in performances between screenings of the Ronald Coleman film "Condemned."

Things weren't what they once were in the vaudeville world just a fleeting three years earlier, but signs of its inevitable collapse hadn't quite set in yet either.

The proposed Eddie Cantor scripted Columbia film never materialized, and it would be three years before he'd appear before the camera again --- for Columbia and for the last time, in an musical novelty comedic short titled "Um-Pa." Although he didn't know it during the holiday season of 1930, Osterman's star would never rise higher than it already had, nor would he live to see the conclusion of that decade.

An audience favorite throughout the 1920's, Jack Osterman's career would peak in 1926 with his contributions to a musical revue, "A Night In Paris," which played the roof garden of New York City's Century Theater (dubbed "Casino de Paris") for 208 performances, an incredibly impressive run for the time. But, as with Osterman himself, the frivolities of 1926 were a world away from the biting winter winds of Syracuse in 1930, and that same year would mark the demolition of the site of his greatest success, the Century Theater itself, leaving nothing but memories and press clippings.

The proposed Eddie Cantor scripted Columbia film never materialized, and it would be three years before he'd appear before the camera again --- for Columbia and for the last time, in an musical novelty comedic short titled "Um-Pa." Although he didn't know it during the holiday season of 1930, Osterman's star would never rise higher than it already had, nor would he live to see the conclusion of that decade.

An audience favorite throughout the 1920's, Jack Osterman's career would peak in 1926 with his contributions to a musical revue, "A Night In Paris," which played the roof garden of New York City's Century Theater (dubbed "Casino de Paris") for 208 performances, an incredibly impressive run for the time. But, as with Osterman himself, the frivolities of 1926 were a world away from the biting winter winds of Syracuse in 1930, and that same year would mark the demolition of the site of his greatest success, the Century Theater itself, leaving nothing but memories and press clippings.

Bittersweet recollections don't buy food and pay hotel bills however, and Osterman plugged on continuously after 1930 --- accepting and fulfilling play dates across the country in theaters that now billed vaudeville performances as an "Extra! No Additional Charge!" feature, as well as in supper clubs, burlesque houses, seaside amusement piers, fun parks, and anywhere else where work could be found for orphans of the vaudeville circuit.

Apparently well liked by his peers (he counted George Jessel and Eddie Cantor as his closest chums) and the press, period newspapers are filled with syndicated "plugs" for Osterman in columns by Walter Winchell and his imitators, that much in the same way they do today, served primarily to keep a name in the public eye and to give the impression of activity, excitement and viability. Sometimes, a photo would accompany such a publicity placement, as it did here earlier in 1930 when Osterman shared the spotlight with actress Esther Ralston in what amounts to a filler.

1935 would see an attempted shot to reclaim prior fame in a new musical revue, "Smile At Me," booked into New York City's Fulton Theater (later the Helen Hayes Theater) in late summer of that year, for which Osterman contributed his own musical material, but it would wither and close after struggling on for only 27 performances.

1935 would see an attempted shot to reclaim prior fame in a new musical revue, "Smile At Me," booked into New York City's Fulton Theater (later the Helen Hayes Theater) in late summer of that year, for which Osterman contributed his own musical material, but it would wither and close after struggling on for only 27 performances.Sometimes, one's failure is seen as a key to future success, which is why in 1937 Osterman (perhaps unwisely) agreed to a syndicated newspaper spread for Kings Features that may have done more damage than any intended good. Illustrated with images of much earlier, and presumably happier days, (even the image of Osterman "as he appears now" seems to be circa 1928), it's as bizarre a bit of showmanship as it is sad. It does, however, give us a now forgotten look at the performer's life as he wished it to be known, as well as a glimpse of a beaming Osterman with his wife and former Ziegfeld girl, Mary Daley.

Two short years later, Osterman would become ill and travel to Atlantic City to recuperate at a time when sea air was still thought to be a cure all, but pneumonia would set in and he succumbed on June 8th of 1939. The obituary wired to newspapers across the country is in stark and rather plaintive contrast --- both in size and content --- to the elaborate spread from 1937.

Two short years later, Osterman would become ill and travel to Atlantic City to recuperate at a time when sea air was still thought to be a cure all, but pneumonia would set in and he succumbed on June 8th of 1939. The obituary wired to newspapers across the country is in stark and rather plaintive contrast --- both in size and content --- to the elaborate spread from 1937.

Following his death, newspapers would dredge up all manner of unpleasant material they could find on Osterman, which suggests that while alive, he could be a formidable opponent and well connected enough to make any efforts at negative publicity a losing and possibly long-lasting damaging notion. The following syndicated show business column, by Charles Driscoll takes publishing ghouls to task following Osterman's death, as well as aiming a well deserved brick at George Jessel, who couldn't resist turning in to what amounts to a "performance" at his deceased pal's funeral.

In the years that followed, Osterman would receive mention, albeit infrequently, in syndicated nostalgia oriented columns of the "I Remember The Good Old Days" sort, but even these would fade by the end of the 1940's and arrival of the 1950's, when his name would make news again --- but only in connection with the tragic death of his wife, Mary Daley.

In the years that followed, Osterman would receive mention, albeit infrequently, in syndicated nostalgia oriented columns of the "I Remember The Good Old Days" sort, but even these would fade by the end of the 1940's and arrival of the 1950's, when his name would make news again --- but only in connection with the tragic death of his wife, Mary Daley.

Years pass, memories fade, and the onrush of time and technology sweep away traces of much of what has come before. It's surprising then, to discover that fate has chosen to preserve Jack Osterman as he was in mid-1930, still youthful, still vibrant... at a time when his greater glories had already passed but the future still held a spark of hope and possible new fame. Although the Technicolor feature film it once accompanied, "Song of the Flame" has vanished, Osterman's short subject "Talking It Over" has the power to transport the observer to front-row center in a theater of 1930 where for a scant seven minutes, the performer moves us between smiles, laughter and wistful sighs. Effortlessly and forever.

###