If it isn't frustrating enough to discover that some of the most intriguing motion pictures of the early sound era are apparently lost forever, then it's even more discouraging to learn that virtually the entire output of a medium that walked hand-in-hand with the talkies as they both took their first tentative steps --- radio, is also gone for good.

If it isn't frustrating enough to discover that some of the most intriguing motion pictures of the early sound era are apparently lost forever, then it's even more discouraging to learn that virtually the entire output of a medium that walked hand-in-hand with the talkies as they both took their first tentative steps --- radio, is also gone for good.Whereas there's always the outside chance that a print, or portions of a print, or even just sound discs may turn up for any number of missing early sound films, the bulk of the radio programming that was churned out --- live --- on a daily basis during this same period is not only gone, but gone beyond recall. Oh, I like to think that all that sound is reverberating somewhere in deep space around about now, and perhaps even being listened to. If so, we can only hope it's all being documented, archived and preserved far better than anyone on this planet thought necessary.

On the evening of March 19th of 1930, it's likely that most radio listeners were tuning into Old Gold Paul Whiteman hour, where they would have had the chance to hear two featured players from the Universal revue film "King of Jazz," performing songs from that production, backed by the magnificent Whiteman orchestra. Similarly, a set of tunes from Fannie Brice's second (and last) starring vehicle, "Be Yourself" would also be given the Whiteman treatment. Glorious sounds, lost to time the moment they were transmitted --- or perhaps transcribed to disc for use within the same week, and then filed away --- and then? (It's honestly almost painful to browse radio broadcast schedules of the period, noting all the shows that were direct products of various film studios or countless others that used material from then current films as content. Why, there's even instances of "direct transmission" from movie theaters, teasing and luring radio audiences by broadcasting entire reels of sound from early talkies. How many innumerable gaps in the shadowy history of this period in entertainment could be filled if only this material had been retained and archived!)

That same Winter evening in 1930, a movie or music fan turning their radio dial might have happened upon a swirling string orchestra rendering "I'm A Dreamer" from the 1929 Fox film "Sunny Side Up," and liked what they heard enough to settle back and let the radio dial alone.

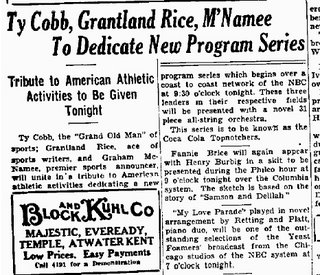

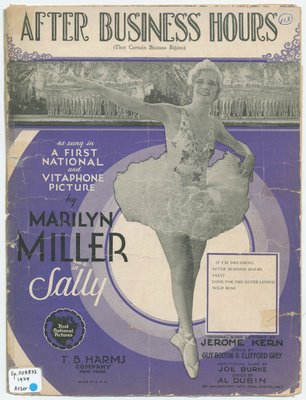

Within moments though, these very same listeners might be back at their dial again --- but this time to tune away from a stilted, scripted interview of sports figure Ty Cobb. Likewise, this same broadcast that might, and surely did, attract casual sports enthusiasts, youngsters and rabid baseball fans alike probably --- within moments --- furrowed brows and sent hands scrambling for the dial when it was immediately followed by an oh-so-dainty rendition of "Wild Rose" from the 1929 Warners film version of "Sally." What were they listening to? What was this?

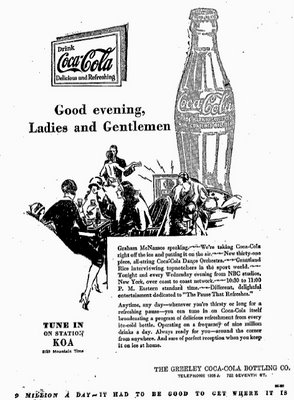

It was, for approximately four months, "The Coca-Cola Top-Notchers," a radio show that combined sweet music, soft drink sales and sports into one unwieldy and unappetizing oil and water concoction.

It was, for approximately four months, "The Coca-Cola Top-Notchers," a radio show that combined sweet music, soft drink sales and sports into one unwieldy and unappetizing oil and water concoction.The premiere broadcast, dating from 19 March 1930 has survived, as does the one that followed, from the 26th of that month. The latter show refers to upcoming broadcasts which either aren't in circulation or haven't survived, but there's no evidence to suggest the show continued any later than late May or early June of 1930.

Additionally, the premiere broadcast is likely not only the oldest surviving, complete and non-transcribed radio shows in existence, but also the oldest musical-variety show existing in a complete format. The second show even includes a station ID break, for WEEI in Boston, which is preceded by a series of chimes: one of the earliest surviving recordings of the NBC chimes, though not the familiar G-E-C chime which evolved shortly thereafter.

NBC Chime - WEEI Boston - 26 March 1930

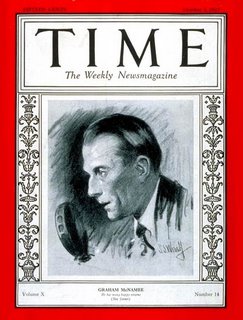

Surviving advertisements for the show (for which there appears only to have been two or three basic designs) and both show announcer Graham McNamee, emphasize the most unusual aspect of the show, which was made one of its selling points: An "all-string" orchestra, led by Leonard Joy, at the time a well known recording artist (and musical director at Paramount) that would bridge interview segments by Grantland Rice, a respected sportswriter of the era, with various figures from the world of sport

Graham McNamee was one of NBC's leading announcers of the 1920's and 30's, and after The Coca-Cola Top-Notchers, he would go on to be Ed Wynn's foil on "The Texaco Fire Chief," a show that enjoyed tremendous popularity and the staying-power that eluded the Coca-Cola effort.

Graham McNamee was one of NBC's leading announcers of the 1920's and 30's, and after The Coca-Cola Top-Notchers, he would go on to be Ed Wynn's foil on "The Texaco Fire Chief," a show that enjoyed tremendous popularity and the staying-power that eluded the Coca-Cola effort.In the surviving episodes of Top-Notchers, McNamee manages to work in the commercials for Coca-Cola fairly well, even with the crude sledgehammer-like copy he was given, no doubt by the D'Arcy advertising agency.

With apologies to sports historians, what all but kills "The Top-Notchers" are, unfortunately, the sports interviews. The interview with longtime Detroit Tigers star Ty Cobb, is a trial to listen to, as it's painfully obvious that Cobb is reading from a script that attempts and fails to create an illusion of impromptu conversation. Cobb is, however, quite a bit cleaned up from the terrifying figure that he often presented to rival ballplayers and others who got into his way.

The second surviving show includes an interview with Stewart Maiden, the mentor of golf champion Bobby Jones, although at this distance in time, the interview is largely of archaeological interest to golf fans.

The second surviving show includes an interview with Stewart Maiden, the mentor of golf champion Bobby Jones, although at this distance in time, the interview is largely of archaeological interest to golf fans.Interestingly, both guests have Georgia connections of one kind or another. Ty Cobb was, of course, known as "The Georgia Peach," and just happened to be a significant investor in Coca-Cola, having bought stock during a reorganization of the company at the end of the Great War, which made him a wealthy man. Bobby Jones had close ties to Augusta National, the famed golf course where the Masters tournament was (and still is) played. Do you get the sense that the first two guests were chosen with an eye toward what would appeal to Coca-Cola executives?

The program musical interludes are, for lack of any other way to describe them, incredibly odd. For one thing, Leonard Joy's arrangements (for the "all string orchestra") seem to be not so much of 1930, but very nearly of the lush orchestrations of the 1950's and even 1960's --- almost bordering on the sound of "Light FM" muzak-type radio. Therefore, it comes as a jolt to suddenly realize that these swirling, soaring strings that might be at home in any elevator, supermarket or shopping mall circa 1975 are playing tunes from musical films of 1929 and 1930.

In the example of the premiere broadcast, offered below complete and intact (and apologies for the very mediocre sound quality!), musical selections include "I'm A Dreamer" ("from that famous talkie, 'Sunny Side Up,' says announcer McNamee,) the sentimental standard "My Gal Sal," "My Sweeter than Sweet" from the Paramount film "Sweetie," "Rosita," a tango, "Wild Rose," from the Warner Bros. film version of "Sally," "Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life," (which was featured in the 1929 RKO film "Syncopation,") and finally, "I'm Following You" from the Duncan Sisters' starring Metro vehicle, "It's A Great Life."

In the example of the premiere broadcast, offered below complete and intact (and apologies for the very mediocre sound quality!), musical selections include "I'm A Dreamer" ("from that famous talkie, 'Sunny Side Up,' says announcer McNamee,) the sentimental standard "My Gal Sal," "My Sweeter than Sweet" from the Paramount film "Sweetie," "Rosita," a tango, "Wild Rose," from the Warner Bros. film version of "Sally," "Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life," (which was featured in the 1929 RKO film "Syncopation,") and finally, "I'm Following You" from the Duncan Sisters' starring Metro vehicle, "It's A Great Life."A solid, enjoyable parade of melody --- but again, there's something about the orchestration and arrangement that doesn't spell 1930 so much as 1960. Delightfully odd perhaps to us, but how I wish we knew what listeners of 1930 made of this.

As noted earlier, the show simply pulled up stakes and vanished by June of 1930. But why? Mark Pendergrast's book, "For God, Country and Coca-Cola" refers to the program, indicating that it had a budget of $400,000, a significant expenditure for 1930. With the looming Depression, this may have been too much for a show with the kind of production value that it had, even for a company that weathered the economic storm like Coca-Cola.

Another possibility is corporate unease with the show. Pendergrast notes that the tyrannical president of Coca-Cola, Robert Woodruff, hated the initial theme music Leonard Joy composed for the show, forcing a change from the original tango-influenced theme to the ethereal (drippy) waltz melody that replaced it. Ironically, this latter version would provide the signature tune for many other Coca-Cola sponsored shows on the radio, according to Pendergast. Coca-Cola's obsession with wholesome, upbeat theme and content for its radio shows may have also been a factor which made it difficult to sustain an early effort such as the Top-Notchers; certainly, the D'Arcy advertising firm was subjected to all manner of headaches in managing radio shows throughout the 1930's.

Another possibility is corporate unease with the show. Pendergrast notes that the tyrannical president of Coca-Cola, Robert Woodruff, hated the initial theme music Leonard Joy composed for the show, forcing a change from the original tango-influenced theme to the ethereal (drippy) waltz melody that replaced it. Ironically, this latter version would provide the signature tune for many other Coca-Cola sponsored shows on the radio, according to Pendergast. Coca-Cola's obsession with wholesome, upbeat theme and content for its radio shows may have also been a factor which made it difficult to sustain an early effort such as the Top-Notchers; certainly, the D'Arcy advertising firm was subjected to all manner of headaches in managing radio shows throughout the 1930's. So, if you're seeking a half hour of "refreshing rest," I can't guarantee that you'll find it in listening to this oddly fascinating example of early radio, marketing cross-promotion and sports history --- but as it's one of our very few chances to listen in on 1930 radio precisely as it was originally transmitted, can you resist?

So, if you're seeking a half hour of "refreshing rest," I can't guarantee that you'll find it in listening to this oddly fascinating example of early radio, marketing cross-promotion and sports history --- but as it's one of our very few chances to listen in on 1930 radio precisely as it was originally transmitted, can you resist?"The Top Notchers" - 19 March 1930

A puzzle: The sheet music for "Sally" (WB-1929) pictured to the left, heralds a song ("After Business Hours") that's nowhere to be found in surviving prints of the film. Has anyone thoughts or information?

Special thanks to friend and supporter, Eric O. Costello of New York City, for his contributions to this post!

###

3 comments:

When I tried the "Top Notchers" mp3, it came up as only 29 sec. of the opening theme. Was there supposed to be more?

As with all audio on these pages, the best route to go is to right-click and "save," thereby downloading them to your HD. The Top-Notchers show is a large file owing to the show's l/2 hour length, and probably would stream very poorly, if at all. If you still run into problems, e-mail me and I'd be happy to send it to you directly.

Jeff, the reason that early radio is so rare is that it was fairly expensive and cumbersome at the time to record broadcasts. Most of the shows that do survive come from aluminum discs that are difficult to play back. These were usually recorded at 78 rpm in multiple parts and the only people who would pay to get the recordings done were performers on the shows to keep for future audition purposes or the companies and advertising agencies involved with the shows to critique them. Around 1935, a less expensive method of recording shows using coated discs became available and recording became more common, mainly for legal reasons - the networks wanted to keep a record of live broadcasts in case questions came up about the content of a show - or to offer a program to a station that couldn't broadcast it in the live time slot.

Post a Comment